Inside Arizona's Punishment System:

Part 1: The Web of Criminalization

Table of Contents

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone

for those of us who cannot indulge

the passing dreams of choice

who love in doorways coming and going

in the hours between dawns

looking inward and outward

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futures

like bread in our children’s mouths

so their dreams will not reflect

the death of ours: …

Audre Lorde, A Litany for Survival

Introduction

In the first report of this four-part series, we illuminate the pathways of entrapment into the Arizona Punishment System. The following analysis reflects dozens of in-depth interviews and hundreds of testimonies from those of us who are directly impacted by this system. We center the voices of incarcerated women, a group rarely invited to the forefront of these discussions. We speak as women and mothers, but mostly as experts, with intimate wisdom of these structures.

In this report, we have identified the policies and practices that capture people by design, as well as the institutional frameworks that foster these practices and their consequences. What we found were shared patterns of the denial of resources and safety, racial and gender marginalization, and omnipresent state harassment and violence. The following report breaks down each of these patterns as we and our peers have experienced them – through targeted policing, the separation of families, and the continued expansion of this web in the name of reform. Together we demonstrate that entry into Arizona’s Punishment System occurs at the convergence of systematically produced vulnerabilities to state violence.

Our analysis begins with a contextual discussion of the punishment system and its reaches. We signal to readers that this industry has grown by systematically depriving certain bodies and communities of social resources and then creating institutions to violently control them. We include insights from the historical construction of this process and the context of Arizona’s nationally infamous system as well as the routes of criminalization and state abandonment that have captured so many of us. These sections move from accounts of predatory policing to family suffering and separation, to the expansion of state capture via heightened surveillance and emerging “alternatives” to incarceration. We pay particular attention to the cyclical fallout for families and communities that must bear the burden of generations of disproportionate state violence. We center our struggles with economic hardship, socially produced vulnerability, racism, patriarchy, and disability to peel back the layers that normalize our criminalization. We seek to reveal what it’s like to come from and struggle for our families and communities ravaged by state “justice.” Our testimonies demonstrate the ways dire and unsafe conditions are reproduced and preyed upon by the apparatuses of the punishment system, which seems to be ever-expanding.

Surviving Between the Fibers: The Web and its Growth

When you see someone being arrested and placed in handcuffs, what comes to mind? Do you wonder what they have done, whether they deserve it, or do you withhold your judgment because everyone should be presumed innocent until proven guilty? Behind every arrest lies a person whose story echoes a fight to exist with dignity. Our research centers these stories—to get to the heart of how it is that over 62,000 human beings are currently living in cages in our state.1 This answer is not easily accessible by outlining charges and crime rates, or discussing “crime-ridden” areas, as many reports do. Rather, we offer the radical proposal that understanding this system requires a fundamental analysis of how it violently reproduces itself and what it replaces in our communities under the misguided notion of public safety. This requires an undeniable recognition that we and others within prisons and jails are members of our larger community, despite being displaced from it. Only then can we interrogate the effects of the vastly disproportionate criminalization of those on which the system feeds.

1. This value was reported in 2018 in the Arizona profile by the Prison Policy Initiative, representing the 42,000 in state prisons; 14,000 in jails; 4,600 in federal prisons; 720 in youth facilities; 170 involuntarily committed; and 740 in Native country. This is in addition to the 76,000 on probation and 7,200 on parole.

The prison industrial complex is an intangible web of individuals, institutions, and ideologies that serve to trap those who become vulnerable to its reach—it extends even as it captures. The ‘prison industrial complex’ is a term prolifically used and elaborated in the writings of scholar and activist Angela Y. Davis (Davis 1998; 2003; 2005), and was first coined by Rachel Herzing, co-founder of Critical Resistance. The ‘prison industrial complex’ are technologies of power represented by surveillance, policing, and imprisonment that are positioned as catchall solutions to economic, social and political inequalities. Once we are in the web, we are targeted, punished, and never actually released. The strands attached to us extend to those around us, clutching our families and communities. This web is strengthened by every arrest, every conviction, and every sentence of incarceration.

Prison scholars Victoria Law and Maya Schenwar (2020) define the expanse of actors that sustain the “carceral web” as “lawmakers, judges, prosecutors, parole officers, and police officers” but increasingly, also “social workers, emergency room doctors, and landlords… teachers.. pastors.. school counselors… psychiatrists.. homeless and domestic violence shelters” and more. The reaches of the web that connect punishment with social welfare mechanisms (welfare here being both wellbeing and state support services) are perhaps the most illuminating threads for how the carceral machine works. The web of capture and punishment is explicitly linked to the oppression of certain communities who, rather than receiving protection under the law, experience deeper vulnerability precisely because of it. Critical geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2007) refers to this process as part of “organized abandonment,” wherein the state has used increased policing and incarceration to effectively dismantle and replace social supports:

[I]n urban and rural contexts, for more than 40 years, we see that as people have lost the ability to keep their individual selves, their households, and their communities together with adequate income, clean water, reasonable air, reliable shelter, and transportation and communication infrastructure, as those things have gone away, what’s risen up in the crevices of this cracked foundation of security has been policing and prison.

(Scahill 2020)

Beth Ritchie (2012) sees the US becoming a “prison nation” that uses “new laws and aggressive enforcement of social norms [to] reinforce…that deviations from normative behavior or violations from conservative expectations should be punished by the state” (p. 17).

The expansion of this punishment web has made Arizona the 5th most incarcerating state, in a nation that holds a quarter of the world’s imprisoned population. Arizona alone imprisons a larger percentage of its residents than do many wealthy democratic nations.2 According to recent reports by Fwd.us, Arizona’s imprisonment rate has ballooned by 60% between 2000 and 2018. In this, Arizona is only outpaced by Louisiana, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Arkansas. Nationally, the rate of incarceration quadrupled over the last 40 years; Arizona’s grew to 12 times its size over the same period (Fwd.us 2018a, p. 1-2).

When we are trying to grasp the expansion of the punishment web writ large, it’s vital to note that Arizona’s system is nationally notorious both for rates of growth and for extremely long sentences. Arizona currently spends over $1 billion in taxpayer dollars annually on the Department of Corrections alone—not including millions spent on policing, courts, private parole or probation subsidies, school resource officers (SROs), or detention facilities and agents. This budget far exceeds spending on higher education (Grand Canyon Institute 2016)3, is double the spending on economic security, and nearly 3x that of child safety (Fwd.us 2018a, p. 4). The punishment system’s web of capture extends its reach through the replacement of social services with accelerating criminalization, constantly capturing new generations. In 2017 alone, people sentenced to prison for their first felony represented 41% of all incoming prison sentences (Fwd.us 2018a, p. 13).

2. AZ has a higher rate of incarceration than: UK, Portugal, Luxembourg, Canada, France, Italy, Belgium, Norway, Netherlands, Denmark, and Iceland, according to the Prison Policy Initiative report on Arizona.

3. According to a 2016 study published by the Grand Canyon Institute, Arizona is one of only four US states (including Vermont, New Hampshire, and New Jersey) that spend nearly twice as much on prisons as on higher education. The study reports: “In 2002, Arizona spent 40% more in the General Fund on universities than it did on incarceration. This year, Arizona will spend almost 60% more on prisons than universities.”

Arizona's Carceral History

The dark history of Arizona’s prison expansion reflects decades of fiscal conservatism mixed with a racist nostalgia for taming the frontier. Distrust of outsiders, recourse to state’s rights, and one of the nation’s most influential “tough on crime” agendas rounds this history out (Lynch 2009). Frank Eyman’s leadership of the Department of Corrections (1955-1972) marked the rise of a rhetoric around using corrections to enforce social stability by controlling “incorrigibles.” Eyman set the tone of social control in Arizona corrections via the degradation of inmates’ dignity- over and above the physical punishment that is incarceration. While such practices were common prior to

his reign, Eyman utilized the press to proudly fan the flames of public contempt for prisoners. In an interesting foreshadowing to conditions under Charles Ryan, in response to an uprising at Florence, Eyman “welded each prisoner into his cell, as the locks had been broken during the riot, where he left them, stripped naked with only a blanket each, for several days. He justified this act to the press by saying that the inmates ‘had to learn to behave’ and needed to realize that as prisoners in his institution, they didn’t have any rights” (Lynch 2009, p. 45, citing Arizona Daily Star, 1958). Eyman also permitted medical experimentation on inmates at Florence men’s prison (Lynch 2009, p. 45).

Then Governor Jack Williams, who saw the shared role of local government and corrections as “saving a society that is facing Armageddon,” endorsed this approach wholeheartedly (Lynch 2009, p. 58). Historian Mona Lynch (2009) argues that the 1977 criminal code reform marked “the first significant incidence in which the symbolic politics trumped the practical in criminal justice policymaking to such an extreme degree within the state” that lawmakers specified their intentions explicitly and publicly toward maximizing “harsh and certain punishment” over budgetary—and legal—pressures (Lynch 2009, 97). Overtly punitive policies that targeted inmate access to programs and increased overcrowding also grew in popularity throughout the 1980s.

Perhaps most infamously, in 1987 Arizona created the first brand new, state-level supermax facility in the nation; by 1999, the state had the second highest use rate of such facilities proportionally in the country. Additionally, Arizona set national precedent by instituting mandatory inmate fees for electricity and “room and board” and re-introducing the chain gang (Lynch 2009, pp. 122, 5). All of this occurred against a backdrop of voter suppression, extended segregation, extreme district-dependent education funding structures, “right to work” policies to halt labor rights, and state social services and welfare spending dramatically below national average (Lynch 2009, p. 24).

While 1 Arizonan in every 13 lives with a current or prior felony (Fwd.us 2018a, p. 3)4, we must understand the extent to which the web of capture and punishment differentially targets those Arizona communities already systematically abandoned by the state. Specific areas routinely experience increased criminalization whereby more police means more arrests and more prison sentences, making the community’s path to prison a self-fulfilling prophecy. As is historically consistent, over-policing, sentencing rates, and longer, disproportionately enhanced sentences are racialized: Black Arizonans are on average given 50% longer sentences for drug possession than whites—and receive the longest overall sentences in the state (Fwd.us 2018b, p. 13). Latinx Arizonans also face disproportionate conviction rates even where arrest rates are proportional to state population (Fwd.us 2018b, p. 16). These practices/patterns of policing and incarceration wreak havoc on the livelihood of communities, from health disparities to reliable employment to secure housing (Fwd.us 2018b, citing Fagan & West 2010; Cloud 2014).

4. This number comes from research conducted in 2010, and has thus likely grown since then. Unfortunately no current numbers exist as these figures are not frequently publicized.

One community that bears the extremely disproportionate burden of incarceration is the neighborhood of South Phoenix.5 Though only representing 1% of the state’s population, the 84041 zip code represents 6.5% of the imprisoned population in all of Arizona, costing the state roughly $70 million annually (Greene 2011). South Phoenix contains multiple “million dollar blocks”6 —areas where the state spends over $1 million annually to criminalize and incarcerate a dense concentration of residents on a single city block (Spatial Information Design Lab, 2008). This community not only stands out in Arizona, but nationally: residents of South Phoenix are incarcerated at 5 times the national rate (6.1 per 100 residents compared to 1.09 per 100) (Center on Media Crime and Justice, 2008). As is consistent nationally and especially in Arizona, this over-policed and over-imprisoned community is predominantly low-income people of color. While Black residents make up roughly 4% of Arizona’s total population, 16.5% of residents of South Phoenix are Black; and Latinx residents make up 62% of the population of South Phoenix, compared to 29% across the state. Additionally, 40% of South Phoenix children under 12 are living below the poverty line, whereas the state as a whole averages 23%. Rates of uninsured residents, education access, and premature infant mortality rates are similarly disproportionate to the rest of the state (Bureau of Women’s and Children’s Health, 2020). These racial and class demographics are not happenstance; they reflect and reproduce the design of Arizona’s punishment system.

5. According to a presentation for the Justice Center Judiciary Hearing for the Council of State Governments, the imprisonment rate for South Phoenix (84041) is roughly 31.8 per 1,000 adults; for jail, 96.5 per 1,000 adults; and for probation, 25 per 1,000 adults.

6. This concept is used widely but most prominently by the Justice Mapping Center in New York.

Arizona prison growth has also been extremely gendered. The female imprisoned population has more than doubled since 2000; the national average rate of incarcerating women increased 19%, whereas Arizona produced a 104% increase (Fwd.us., 2018c). The majority of women incarcerated in Arizona are older, white, Latinx, and those from rural areas (Ibid.). Women have been found to report far higher rates of trauma, mental health issues, and substance use (Ibid. citing S. Lynch et al., 2012; Law, 2009). These are in addition to overall patterns regarding organized abandonment and hyper-policing of racialized, low income communities.

Given the gendered experiences of social vulnerability to which women are disproportionately subjected, our stories and those of so many others reflect intimate traumas. But as poet and activist Aurora Levins Morales reminds us, “examining psychological trauma inevitably leads us to the most widespread source of trauma, which is oppression” (Morales 1998). It is through this cognizance that we are hyper aware of multiple simultaneous levels of violence operating through Arizona’s punishment system.

While we know that our conditions and actions are contextual, we have often faced the punishment system alone and afraid. Our hopes have been diminished and the death of our next generation becomes more of a reality every passing day that the web becomes broader. While we have historically been criminalized for failing to conform to patriarchal standards as women and mothers, and while prisons remain institutions built by and for men, we stand in direct confrontation with the gaps in awareness regarding our lived experiences and the power structures which silence them. We share the following stories and analyses from “the belly of the beast” in order to record a new narrative, of some of the brave women who, together, form a small but integral part of this enduring, violent history of the disavowal of safety in favor of punishment.

Community Targeting

In Arizona, as nationally, concentrated police presence disproportionately targets residents of cities’ lowest income, predominantly non-white neighborhoods. Latinx residents have faced discrimination since Arizona’s territorial days, most recently enduring Sheriff Arpaio’s reign of profiling and harassment fueled by emboldened anti-immigrant racism and culminating under SB 1070 (Casey et al., 2020).

Racism in police forces is well documented, and yet this documentation has not altered the practice. Recently the Phoenix police department underwent an investigation regarding racist and violent social media postings as part of a national study by the Plain View Project. The study revealed over 170 problematic posts made by over 70 officers from the Phoenix department alone. These resulted in paid suspensions and trainings; only one officer was fired (Casey et al., 2020).

Racially targeted policing is perhaps most visible in relation to officer shootings: according to a Department of Justice special report from 2018, police-initiated contacts were twice as likely to result in shootings of Black and Latinx residents than whites (E. Davis, Whyde & Langton, 2018). In fact, in 2018 Arizona once again became nationally infamous when more residents were shot at by officers in Phoenix than in any other US city. The Arizona Republic conducted a review of 8 years of police shootings which demonstrated consistent patterns: Black and Native American residents were shot and/or killed by police at double the rate of whites in Phoenix (Ibid.).

Throughout our research, we heard ample accounts of the trauma that discriminatory policing caused for women’s families and communities. Contrary to the motto “to protect and serve,” we and our participants know, and will show you here, the systemic and intimate ways the police mete out violence in the name of public safety. Many of the women we interviewed were children when they were first followed, harassed, and intimidated by officers patrolling in over-policed communities. Constant surveillance instilled in them a recognition and the fear that according to the state, their lives warrant suspicion.

“Agents of Neighborhood Bigotry”

Scholar of policing Alex Vitale (2018) argues that this takeaway is key to the way police keep under resourced communities on edge; as part of the “warrior mentality” where “police often think of themselves as soldiers in a battle with the public rather than guardians of public safety.” This is evident in the frequency of police shootings of unarmed civilians across the nation. He argues that the introduction of millions of dollars’ worth of military grade vehicles and weapons, garnered through political projects like the War on Drugs, “fuels this perception, as well as a belief that entire communities are disorderly, dangerous, suspicious, and ultimately criminal” (Vitale 2018, p. 3).

We found that it is this violence that initiates many into the punishment system because the police create, enforce, and reproduce criminality, regardless of behavior and based primarily on race, on gender, and most commonly, on socio-economic class. The practices of targeted policing have a not-so-distant history of explicit policy formation through “broken-windows policing” and its practice of “stop and frisk.” Broken windows theory was popularized in the early 1990’s and framed as a community minded alternative to aggressive policing. It theorized that community disorder, such as broken windows, leads to a proliferation of minor and major crime. The theory of broken windows was mapped on to the bodies of community members who were then pathologized as inherently “criminal.” Stop and frisk policing emerged from broken windows theory.

George Kelling, researcher on these theories, initially promoted the efficacy of the broad idea behind broken windows: that by concentrating police patrols on misdemeanor crimes and perceived order, violent crimes would be lessened. He soon recognized that ‘order’ meant the criminalization of race and poverty; the overt practices of stop and frisk come from the targeting of panhandling, loitering, and simply “looking suspicious” (Vedantam 2016)7. Worse, Kelling’s early fears regarding police abuse of authority became evident as part of the fabric of the police practice. “How do we ensure,” he wrote, “that the police do not become the agents of neighborhood bigotry? We can offer no wholly satisfactory answer to this important question” (Ibid.).

7. NPR’s reporting on this history links the lack of clarity around what constitutes “order” as directly translating to racism: “Even more problematic, in order to be able to go after disorder, you have to be able to define it. Is it a trash bag covering a broken window? Teenagers on a street corner playing music too loudly? In Chicago, the researchers Robert Sampson and Stephen Raudenbush analyzed what makes people perceive social disorder. They found that if two neighborhoods had exactly the same amount of graffiti and litter and loitering, people saw more disorder, more broken windows, in neighborhoods with more African-Americans.”

Our research participants echoed this resignation, demonstrating the ways discriminatory policing itself served to criminalize them due to the way they looked and the neighborhoods they lived in. One of our first interviewees, Sofia, shared with us her experiences navigating constant police presence as a young teenager in her neighborhood and while incarcerated in a youth prison. Sofia would hang out outside in her neighborhood after school and often walked home with her friends. At any time, police officers would stop them, search their backpacks and harass them. She shared:

I would run and so would my friends, for no reason at all—just because we knew they were coming for us. We weren’t even doing anything wrong... In juvi, one of the male CO’s—six feet and two inches tall—beat me up so bad because I had an argument with another girl. I think I cussed at him. Made me hate authority figures. I was just a kid and angry at the harassment.

(Sophia interview, 2019)

Sofia suggests that disrespect of people the police perceive as under their authority and control is inherent to the practice of policing- both outside in the free world and inside the community of prisons. One of Sophia’s release conditions was that she not associate with documented gang members. Sofia was made to fear spending time with friends she had known since kindergarten. She was criminalized for associating with her peers, isolated, and became more susceptible to ongoing police harassment in her neighborhood.

Valentina experienced very similar targeting in her early teenage years. She watched the police violently assault her sixteen-year-old friend because of suspected gang activity. The “gang unit” pulled over teenagers walking around the neighborhood, interrogating them about being gang affiliated based on race and class.

This furthered Valentina’s belief that the police were not to be trusted. The police treated the neighborhood children as if they were not to be trusted. As she put it:

You just kind of feel like you don’t have the right to be. You know, you’re going to be harassed. This is why I think I’m in a constant state of like, I’m a bad person or I’m a criminal: I’m seen as a criminal... You were always on the run, constantly. But you didn’t know why... You’re born into it. You’re born into a state of paranoia.

(Valentina interview, 2019)

Valentina ultimately learned that running was a better option than being bullied and potentially assaulted, as she had watched. Wisely, she chose to adapt for the sake of self-preservation in the face of indiscriminate harassment: “we can’t trust the police; it’s us against them in my hood” (Valentina Interview, 2019).

For several of the women we interviewed, their first interactions with the police were when they called for help and were instead met with an officer’s disregard and their sole determination to make an arrest. Lily was first arrested under a dual arrest statute when she called the police during a physical altercation with her partner (Lily Interview, 2019). While such statutes create an image of impartiality, the all-too-frequent consequence is that the victim is not believed and is instead entrapped in the system for calling the police. This practice is often discouraged by policymakers and organizations for survivors. Another interviewee, Zumaya, had also never encountered the police before she called them for help. Her ex-husband and his girlfriend had kidnapped her infant son and threatened to keep him hidden until Zumaya signed over custody to his father. The police told her there was nothing they could do. At that response, Zumaya’s mother became frantic and rather than console her or address the situation for which they were called, the officers handcuffed her, arrested her, and charged her with assaulting an officer. The police also carted off Zumaya’s elderly mother and did nothing for her son (Zumaya Interview, 2019).

Our research reflected that the overwhelming majority of our participants were subjected to disrespectful, profiling policing practices in their communities. For those of us from neighborhoods like these, the police introduce us to this system by treating us like threats even when we are in need of help. We are conditioned by the police that we carry in our bodies a threat of criminality and, from then on, we become the population that this system targets repeatedly. This threat is largely determined by our race, class, and the profiling of the neighborhoods in which we live. The ability to challenge these practices, Vitale (2018) argues, is a matter of political capital, which has been historically withheld from abandoned communities subjected to targeted over-policing.

Lawyers advocating for the diverse makeup of Phoenix’s newly minted citizen review board argue that this difference in political capital is key:

People from heavily policed communities are not only more likely to be invested in helping the police reform, but also simply have more information on how the police behave... People from ritzy Phoenix communities can easily influence politics through their greater money and access to officials, but the voices of poorer neighborhoods are frequently excluded.

(“Police Review Board Must Represent”, 2020)

However, state lawmakers have swiftly acted to ensure citizen oversight boards, which have been sought in several Arizona cities following worldwide protests for racial justice in 2020, reflect the political interests of police first and foremost. Already successful bills require that citizen boards are comprised of 2/3 active officers, while the few remaining civilian members will be required to undergo 80 hours of police training indoctrination.8 While the extent of police violence, qualified immunity, and community oversight projects is beyond the scope of this report, it is important to take note of the grave lack of accountability that serves as the backdrop to the abuses our research reveals.

The guise of safety and dignity for some has meant the discriminatory treatment of others who are continually subject to disproportionate vulnerability to state violences. Alex Vitale (2018) reiterates how this process grew directly out of broken windows ideology, “and is at root a deeply conservative attempt to shift the burden of responsibility for declining living conditions onto the poor themselves… [with] increasingly aggressive, invasive, and restrictive forms of policing that involve more arrests, more harassment, and ultimately more violence” (Vitale 2018, p. 7). Scholar Lisa Marie Cacho argues that the criminalization of gang activity, for example, is inherently connected to the preservation of whiteness and class status because it “simultaneously valorizes middle-class America and also validates the historical and present-day practices that work to isolate, segregate, and alienate criminalized neighborhoods of color” (Cacho 2012, p. 63).

Cyclical Cause & Effect

For decades, poor people—particularly people of color—were immobilized in city centers through federally enforced redlining. Redlining is a racist practice that places goods and services out of reach for people of certain races or from certain geographic areas. Redlining legalized segregation far into the 1980s (Rothstein 2017). Redlining intentionally restricted housing and employment opportunities for neighborhoods of color, hit the hardest by increasing globalization that has outsourced work, especially previously unionized work, to the global south. “As job cuts hit these communities,” Julia Sudbury, co-founder of Critical Resistance and prominent prison scholar explains, “they were devastated by pandemic rates of unemployment, a declining tax base and resultant cuts in social, welfare, educational and medical provision” (Sudbury 2005). The geographical lines officially drawn through redlining, gentrification, and other zoning practices have extended the resounding effects of organized abandonment across generations (Gilmore 2007).

Policies like redlining and cuts to social welfare during the 1960s were paired with increasing public fear of resistance from people of color, epitomized by Black power movements demanding just resources for their communities (Alexander 2012; Gilmore 2007; Berger 2014). At the height of Black power and multiracial civil rights organizing specifically challenging economic and social inequality, coded tropes like the “welfare queen” and the “dangerous criminal” became popular as President Lyndon Johnson waged his “war on poverty”. This was largely inspired by President Nixon, who contended that the US was at war with an “enemy within” (Alexander 2012, pp. 40-58). While Johnson’s administration promoted the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, it also promoted programming informed by the Moynihan Report, an extensive articulation of the pathology of the Black family written to justify racist ideology and policy. White journalists, theologians, and social scientists like Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Edward C. Banfield, and James Q. Wilson explained “black poverty as a fact of American life and crime and violence as somehow innate among African Americans” and subsequently called for the “divestment from community action programs and other social welfare initiatives,” to be replaced by police and prisons (Hinton 2016, p. 21). The Moynihan Report was used as a rationale for both supporting and monitoring Black communities who were deemed incapable of self-determination. This reflected direct undermining of Black power organizing that served the needs and dictates of the abandoned communities for themselves. As author Michelle Alexander articulates, “Civil rights protests were frequently depicted as criminal rather than political in nature, and federal courts were accused of excessive ‘lenience’ toward lawlessness, thereby contributing to the spread of crime” (Alexander 2012, p. 41) This had the increasing effect of legitimizing racist sentiment against those already marginalized by racist policies, and illuminated the connection between poverty conditions, the demands for justice and safety arising from them, and the response of criminalization.

The effect on policing followed in step. Arizona’s own Barry Goldwater built upon this energy in his 1964 presidential bid, calling for “tough on crime” solutions to control and reprimand the “mobs in the street” (Alexander 2012, p. 41) The Watts riots erupted in South Central Los Angeles the following year, in protest of increasing racialized brutality from police. White terror spread following riots in Newark and Detroit, which were contemporaneous with rising student anti-war protests. Then in 1968, riots ensued in 125 cities following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Racist fears that considered this resistance criminal sparked rampant calls for “law and order.” The move to increase criminalization in communities of color was thus solidified. Historian Elizabeth Hinton (2016) has pointed out that Johnson’s signing of the Law Enforcement Assistance Act in 1965 eventually institutionalized the powerful Law Enforcement Assistance Agency under Nixon by 1974 and the Safe Streets Act of 1968 as key policies in legally codifying racist policing (Hinton 2016).

The practice of responding to struggling communities with heightened surveillance and punishment became normalized, even as such conditions worsened. Law and Schenwar write: “This drive to disappear certain groups of people—including those who might otherwise need public aid or services—coincided with the demolition of the social safety net in the 1980s and 1990s” (Law & Schenwar 2020, p. 15). As we will discuss further in our second report, this era framed many significant sentencing structures that multiplied sentence lengths and broadened categories of criminality in a concerted effort to incarcerate more people. The incarceration of economically marginalized people proliferated through increased policing in predatory ways. Some of the most violent measures of racialized “crime control” were exerted under Nixon, including “Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets” (STRESS) in Detroit and the federal COINTELPRO operation (Hinton 2016, pp. 192-205). Under Nixon, the powerful Law Enforcement Assistance Agency assumed vast social welfare responsibilities and made access to such resources contingent upon police interaction and surveillance. The Ford administration oversaw the implementation of means of predicting crimes by locating “potential criminals” among Black youth, primarily through interactions in schools, after-school programs, and housing project mini-stations (ibid. p. 178; 222). These measures, Hinton (2016) argues, were key in creating the crime against which the Wars on Crime and Drugs were waged. Following this, the incarceration web and its warehouses, jails and prisons expanded exponentially (ibid.)

How does one begin to unravel the narrative of law & order? It is unfortunately easy to normalize the practices of targeted policing and criminalization of race and class without understanding history. Our research demonstrated the generational effects of these practices, from constant police presence in our communities to the insurmountable degree of state violence our families face once someone has been entrapped in this system. We found that the pattern of generational incarceration is directly attributable to the state’s systematic practices of generational abandonment and capture—the ways the web expands and contracts. The attempt to meet dire needs with punishment instead of support only exacerbates these generational effects.

It is estimated that roughly 88% of incarcerated women in Arizona currently suffer from “moderate to intensive substance abuse treatment needs,” while national research reveals that two out of every three families is unable to meet the expenses of basic livelihood while a family member is incarcerated (Fwd.us 2018c)9. As we will expand upon further in our other reports, imprisonment has been shown to worsen, rather than resolve, financial and health needs.

9. Data from Fwd.us report “Arizona’s Imprisonment Crisis: The Harm to Women and Families.” Citing a study by the Arizona Department of Corrections and research from the Ella Baker Center regarding the costs of incarceration.

One of our interviewees, Donna, shared the ways familial incarceration harmed her family and her future. For years, Donna’s mother was in and out of prison. She struggled with addiction and poverty and got by doing sex work. Her mother became pregnant during her last incarceration, after she had been repeatedly sexually assaulted by a corrections officer employed by Perryville. Donna was born in the prison and was taken away as an infant, given to her aunt to be raised. The trauma of the assaults and losing Donna caused her mother to spiral into deeper to substance dependency. After a brief release, she was incarcerated again, and committed suicide while Donna was still very young. “My mother was treated as if she was a monster,” Donna said. The effects of her incarceration only inflicted further violence through control and stigma. “And I know that rejection now, being an adult. It probably severely added to her lifestyle and wanting to cope with society and our family’s rejection… she ultimately took her own life” (Donna Interview, 2019). As Donna struggled to get by without support, this unbearable and unresolved trauma made her more vulnerable to the invisible web of the punishment system.

Now serving a 10 year sentence, Donna recounts:

I was still feeling something very empty trying to understand the loss of my mom... it was heavy on my heart.

(Donna interview, 2019)

After Donna survived a brutal domestic attack by her husband, who strangled her so badly he damaged her vocal cords and she was unable to speak for weeks, Donna fell into deep and dangerous depression. She found herself traumatized, unsupported and in dangerous settings surrounded by drugs, just hoping to cope with depression by “being around people who made me feel better, made me feel alive, because I was so dead inside” When Donna was arrested, her child was taken away from her, in the same way and by the same system that separated her from her mother.

I grieved and cried so hard from the loss of them taking my baby out of my hands at 2 in the morning.

(Donna interview, 2019)

Lanae shared her family’s experience with generational entrapment and her fears regarding the fate of her young daughter. Lanae was left by her mother at the age of seven and did not know at the time that her mother was beginning to use crack and developing a dependency.

Lanae’s mother was first incarcerated in the 80s and was in and out of prison throughout the next twenty years. As we have found is common, her addiction did not improve but worsened through her multiple incarcerations, lasting throughout Lanae’s childhood. Lanae was raised by her father, who had to work long hours to support her and her sisters. Lanae reflected, “He did the best he could to financially support us in the absence of my mom” (Lanae Interview 2019). The effects from the loss of Lanae’s mother to the punishment system damaged Lanae’s mental health, her family’s financial status and, now that Lanae is imprisoned, her own daughter’s wellbeing (Lanae Interview 2019).

Our research demonstrates that incarceration affects entire families by removing yet one more source of economic and emotional support from families and communities often already marginalized and targeted. Individuals, families, and communities are burdened with a distinct disadvantage due to the loss of their people. When we reflect once more on the political bases for criminalization, the targeted generational effect of such violence is maddening and often inescapable.

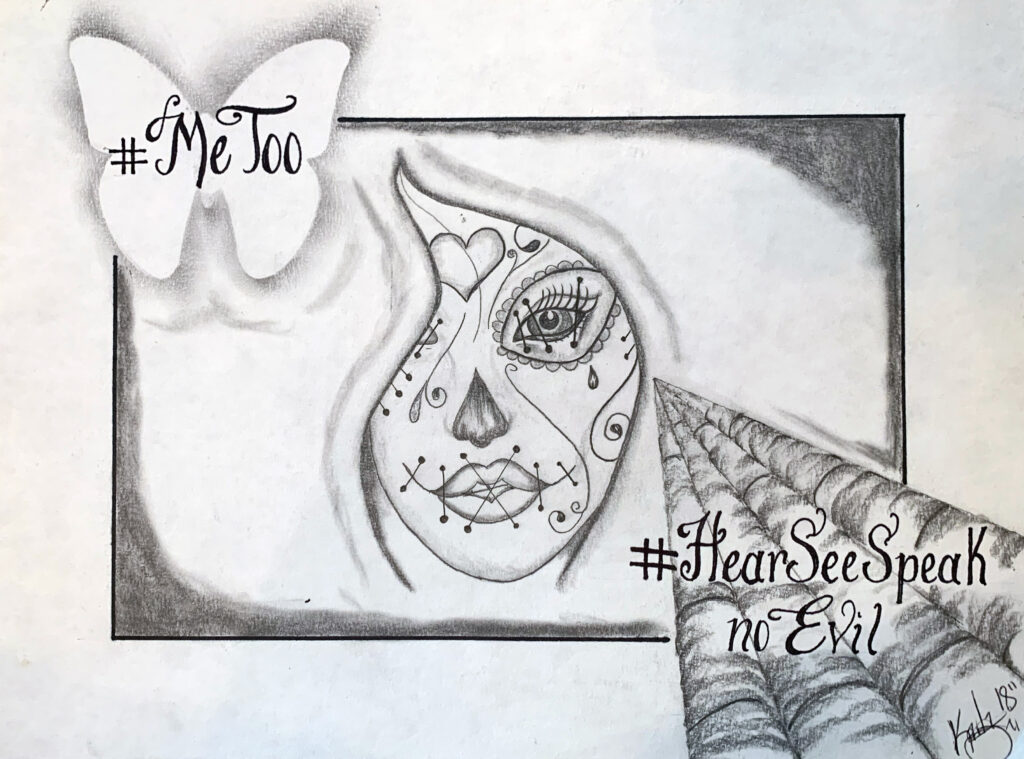

Trauma and Social Vulnerability

The punishment system disproportionately entraps those who have experienced trauma and financial hardship. Exceedingly often, women caught in the web have histories of sexual, physical, and/or emotional abuse; every single one of our female participants reflected this pattern. In our third report, we will share more specific ways the experience of incarceration replicates the structure of abusive relationships but suffice it to say for now that prison is not a place to heal. Nor is it a place to address poverty or dependency. Poverty, like experiences of abuse, has been shown to be disproportionately worsened by incarceration. A national study by the Ella Baker Center found that “poverty, in particular, perpetuates the cycle of incarceration, while incarceration itself leads to greater poverty.” This pattern is reflected in both prison facilities and new admissions to jails; “Estimates report that nearly 40% of all crimes are directly attributable to poverty and the vast majority (80%) of incarcerated individuals are low-income. In fact about two-thirds of those in jail report incomes below the poverty line” (DeVuono-powell et al., 2015). Our research on the effects of interpersonal and state trauma illustrate the ways the punishment system serves to criminalize those seeking refuge and stability.

Sofia ended up in juvenile hall by the time she was 15. She was raised by first generation Italian immigrants who both worked long hours. Her mom was married to her father at the age of 16, having been emancipated by the court due to physical abuse from her father, Sofia’s grandfather. Sofia describes the path in her youth from coping with trauma to getting caught in the web:

Being young parents was hard for my mom and dad. They didn’t have a lot of patience with us and hit us a lot. At age 13 I went nuts and didn’t listen. I had a boyfriend my parents didn’t approve of. The physical abuse got worse so I turned to my friends. When I didn’t want to stop dating my boyfriend, it got really bad. Move forward a few years and the incident that landed me in juvi was when a group of male officers jumped on top of me one day. As I struggled to get free, one lied and said I hit him so that I could be detained. Then they hit me with stealing my parents’ car. My parents owned it but they gave me that car... I look like shit on paper to this day. I am now 43. My first time in prison was at 30. This is my second time. My son has been to prison. I am serving 15 years for marijuana. My life has been a rollercoaster.

(Sofia interview, 2019)

Sofia reflected that her abuse affected her ability to assess risk and her ability to form healthy relationships. So many of our lives were propelled in these directions because we lacked support and resources.

Zumaya became overwhelmed and burdened by her finances and the need to support her family when she was only 23. Her husband decided to quit his job and go to school full time. She made a choice to pay herself a little extra so she could buy diapers and put food on the table. Once her employer became aware, they pressed charges

and arrested her. She was sentenced to 9.75 years for fraudulent schemes. But her incarceration wasn’t her only punishment; Zumaya was pregnant at the time of her arrest and gave birth in prison. She describes the dehumanizing experience: “I was chained to the bed and they ripped him out of my arms. I did not get to heal from that trauma” (Zumaya Interview 2019).

No matter their age, women are often disproportionately burdened with the responsibility to support and protect their families. We have found that this is especially true among us.

One of our other interviewees, V, described how ever since she was young, she carried the weight of her family and their struggles. She managed a lot of the household duties, from cleaning to bills to grocery shopping, to making sure her siblings did their homework. When V was eleven, her 16-year-old brother was shot as a bystander to gang violence at a party. Her mother lost herself, and her father’s drinking and his mental and physical abuse worsened. Her mother, plagued by grief, chose to check herself into a facility, leaving V, her two little sisters and three older brothers in the care of their father. While her mother was away, V took care of everyone. She reflected on that time with us: “Why did I have to be the one responsible for all of that when I was just a kid? And my sisters didn’t understand. My little sister kept waiting for my brother to come home” (V Interview, 2019).

V’s youngest sister attempted suicide after their brother’s death, first at age eight and then again at age ten. V caught her using meth at thirteen. Navigating all of this compounded trauma affected their entire family. The trauma of losing her brother stays with V to this day. As she said, “There was always a void inside me and I knew that void was not being able to ask my older brother for guidance” (V Interview, 2019). Her family’s inability to process his death caused her to struggle with intense anxiety.

Every time my parents would fight, I was the one who would jump in. And so I’d catch a beating along with my mom. I did that for years, always did, and it kind of messed my mind up... I’d have nightmares. I’d wake up in cold sweats and couldn’t sleep.

(V interview, 2019)

As we pointed out above, every one of the women we interviewed had experienced some form of abuse during their lives prior to incarceration. This combined with gendered expectations to make do, no matter the circumstances, reflect the way structures of oppression intersect – to be female and in poverty and criminalized. Jill McCorkel, a scholar on women’s imprisonment, writes:

Women are expected to take ownership of their problems and resolve them by learning how to make the ‘right’ choices even when, in many instances, the situations they find themselves in are not an outcome of choice.

(McCorkel 2013)

No matter the situation, our research also found that women are disproportionately criminalized for being unable to protect their children. When these patterns collide, the effect on lives is overwhelming.

Angie’s story is hard to bear. She shared with us: “To say some of the things that I went through in my childhood were traumatic is really a gross understatement. It was sexual abuse. It was physical abuse. It was emotional abuse… It was the things nightmares are made of” (Angie Interview, 2019). Angie attempted suicide for the first time when she was twelve. She kept her abuse secret for all of her adolescence, trusting no one and hoping she could protect herself. “I really felt like at 15 I wasn’t gonna survive to 18,” she said (Angie Interview, 2019). This fear almost became a reality, but she was brave enough to escape for the first time. Still, her struggles left her with nowhere safe to land. She shared:

I was just an incorrigible teenager who ran away from home. They put me in a shelter. We went to court. My grandmother stood up in court and said she couldn’t take care of me. My father was scared to death of the things I was going to say. They sent me back to my aunt’s where I had just tried to commit suicide. And I probably stayed for about, maybe six more months, and then I ran away from home.

(Angie interview, 2019)

Angie was never able to find safety. As a scared child, she hitchhiked from Florida to Arizona, where she discovered she was pregnant. An older man took her in and abused her and her son. Her nightmare had come full circle. As a result of failing to protect her child from this man, Angie is currently serving a 61-year sentence for harm he inflicted on her son. She was 17 when she was arrested.

The generational effects of trauma can be devastating. Underlying issues are confined to the privacy of the home, and women’s responses are then individualized and criminalized.

As poet Aurora Levins Morales writes, oppression operates by “making it look like the reason we’re thirsty is not that we’re being denied water, but our own lack of initiative in the midst of plenty.”

(Morales 1998)

So many of the women we interviewed were not the first or only ones in their families to experience abuse or poverty, or to struggle to cope with generational traumas resulting from racism and sexism. Whatever these women’s charges are, we must remember that we can be both targeted and do harm—and we include you, our readers, in this assertion. We have to hold both in order to envision the justice that is actually needed, which must include social supports and real processes to make amends. And we must confront that a devastating percentage of women in prisons have pasts that are inconceivable to confront in the violent environment of prison. How do we heal?

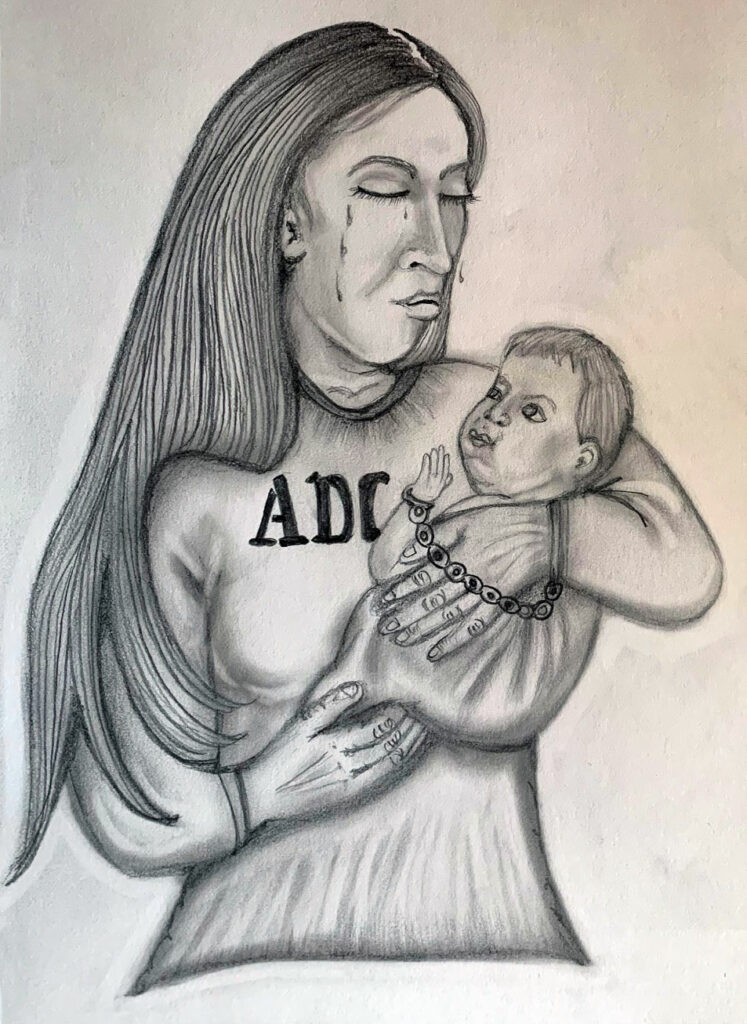

The Battle for Parental Rights

When a mother is arrested, she not only faces her own entry into the punishment system, but this entry also often means the loss of her children to another industry: the foster care system. Like the consequences of incarcerating a providing member of a family in predisposing others to the web of the punishment industry, children entering the foster system are predisposed to state surveillance and deeper insecurities. While Fwd.us recently published that 53% of their study’s respondents had a dependent, minor child, over 80% of the women we interviewed did (Fwd.us, 2018c). Scholar Mariame Kaba has referred to the foster care system as the “child kidnapping system”—“a set of practices that break apart families and punish marginalized people, much like the prison system itself” (Law & Schenwar 2020, p. 124). This characterization is relevant given the rapidly expanding use of both foster care and the total severance of parental rights.

Family separations through foster care increased 10% between 2012 and 2016 (from 387,600 to 437,500) and total termination of parental rights increased by a dramatic 60% during the same period. The federal government spends roughly $7 billion annually reproducing foster care and adoption institutions, but less than 8% of that amount ($546 million) on child abuse prevention and family preservation programs (ibid., p. 132).

Both short and long sentences sever bonds and destroy families. Arizona has one of the highest rates of adoption and does not offer reunification when a mother is incarcerated. As Sofia experienced, “They made it very difficult for all of the women to reunify with the standards that CPS requires” (Sofia Interview 2019). None of the programs that are required for reunification are offered at the county jails. Donna

describes these hurdles:

After spending 21 months (almost 2 years) in Estrella Jail in Maricopa County fighting for my freedom, I was also trying to keep my 5-month-old son from getting taken away by CPS. During this time of being in custody, CPS was requiring specific steps to complete family reunification including classes and testing. However, the jails did not afford such opportunities to support child/parent reunification due to my classification level. After multiple grievances and attempts to find outside resources to meet the CPS requirements with no luck... I was then sentenced to 10 years in prison. My child was under 2 years of age, which allows CPS to support the severance process and adopt out quicker... This moment felt like death. I cried and cried. I couldn’t even say goodbye to my baby boy who was only 5-months-old. I am still devastated, 5 years later.

(Donna interview, 2019)

The hurdles to reunification indicate that the revocation of parental rights is an unspoken sentence of its own.

Sofia also struggled with systemic obstacles and, like Donna, lost her child as a part of her sentence to incarceration. Her daughter was only 1 year old when Sofia was sentenced to 2 years. After completing parenting courses and all mandated requirements, her daughter was adopted just a few months before her release.

When I got out, nothing worked — Prozac and other anti-depressants. I couldn’t stop crying for the loss of being a mom to my three-year-old.

(Sofia interview, 2019)

Some children stay in foster care or are left in group homes, and are certainly left with feelings of abandonment. Some get split up from their siblings. Sarah’s childhood echoed this process. She was taken away and put in foster care, and all four of her siblings were separated. “I was so lost my grades slipped, I was angry and kept running away. I was trying to find my mom and didn’t know how to find her. It was the end of my world” (Sarah Interview, 2019). Sarah is now serving a 10-year sentence. Her parental rights were also severed, and her daughter now lives with her sister’s adoptive mother. As this shows, the multi-generational cycle hinders families and communities in ways that are devastating, and somehow accepted as normal, collateral damage by the punishment system.

We aren’t giving up our kids, they are being taken away, stolen from us.

(Sofia interview, 2019)

Foster Care and the Web

Studies have demonstrated that children in foster care are more prone to struggling due to a lack of security. Additionally, exposure to institutional control in place of family care has been shown to integrate children displaced by the state into the punishment system’s web. Law and Schenwar (2020) cite a University of Chicago study that demonstrated that “the majority of former foster youth (43% of women and 74% of men) surveyed had been incarcerated by age twenty-six” (Law & Schenwar 2020, p. 131).

Those of us entrapped in this system can truly see the devastation that incarceration imposes and the root of why socioeconomic, educational, and health disparities are getting more extreme than ever. Rather than radically approaching social issues like these with a socialized response, we individualize, pathologize, and criminalize. We use prisons as warehouses for the people we don’t want to confront we’re failing. People are not afforded any real opportunity to heal from trauma or find routes to rectify harm and caging a traumatized person does not help. Incarceration causes more than a ripple effect; it so often deliberately includes the entrapment of our next generation. The criminalization of women especially points to this unspoken and related means of punishment. Incarceration devastates families and communities long before, and long after, actual sentencing.

Expanding the Web

In their recent book, Prison by Any Other Name, Victoria Law and Maya Schenwar extensively research various modes by which the punishment system has proliferated in the name of reform. These include the correlation between social services and policing, as described above, as well as emerging tools like electronic monitoring, drug courts, mandatory treatment programs, sex offender registries, foster care systems, expanded and militarized policing, and in-school policing and surveillance. These ancillary forms of punishment and surveillance blur the lines upheld by prison walls. They warn readers interested in dismantling the reaches of the punishment system of counter-productive reform efforts; they write: “often, limited reforms—instead of shrinking the web or taking it down—weave in new strands of punishment and control” (Law & Schenwar 2020, p. 9).

These varying manifestations of the criminal punishment system raise the question of what defines a prison. Is it bars and steel? Bland khaki uniforms? A door that locks from the outside only? Is it the eyes of authority probing you at all times? Is it the hands of authority, manipulating you, hurting you, rendering you ‘criminal’? Or is it more amorphous: a combination of the ways that the state acts on people—in particular, marginalized people—without their consent? There is unique gravity to an actual prison sentence, the violence of locking a human being in a cage. Yet the system is broader than the buildings called ‘prisons.’ Manipulation, confinement, punishment, and deprivation can take other forms—forms that may be less easily recognized as the violence they are. (Law & Schenwar 2020, p. 8)

The overshadowing of conditions of marginalization in favor of “tough on crime” ideology and policies has historically affected progressive reform efforts. Angela Y. Davis reminds us that the prison itself was a mode of reform – originally from public, corporal punishment and later from enslaved and convict labor (Davis 2003). Today, calls for reform are shared between conservative groups like the Koch brothers and the Right on Crime initiative and liberals alike, all of whom echo the sentiment that prisons indeed must exist, but should be prioritized for those “people we are afraid of.” Even proposed reforms that fixate on “offender redemption” reproduce the same logics embedded within the deeply violent Moynihan Report upon which Johnson, Nixon, and Ford relied to rationalize racist policing and incarceration practices (Law & Schenwar 2020, p. 4). Law and Schenwar argue:

This emphasis on ‘redemption’ tends to ignore or minimize the prison nation’s foundations in structural oppressions such as racism, classism, and ableism. Instead, it suggests that the current brutal form of punishment can be replaced in certain circumstances (usually involving people whose crimes are deemed nonviolent) with a less brutal, more compassionate ‘alternative,’ while still placing guilt and blame squarely on the individual. (p. 9)

Studies have shown that reforms that integrate the punishment system’s web of surveillance into communities typically increase repetitive capture. Law and Schenwar (2020) cite a 2018 study by the Brookings Institution that demonstrated that “intensive supervision actually increases, rather than decreases, the chance that someone will be rearrested and reconvicted” (ibid., p. 35; Doleac 2018).

Significantly, some reforms actively create new, lucrative modes of criminalization, entrapping people who would previously have remained free. Electronic monitoring is one such reform, proliferating with the increasing use of probation as an alternative to incarceration. The US probation rate now outpaces the European rate by over 400%, while “A 2012 analysis in the Washington University Journal of Law and Policy notes that… if electronic monitoring was not an option, ‘at least some of these populations would not in fact be incarcerated or otherwise under physical control’” (Law & Schenwar 2020, pp. 89; 30). The use of electronic monitoring for immigrant detention services has ballooned its industry and profits. BI Incorporated, one of the US’s primary monitoring corporations, served Immigration and Customs Enforcement for just under $1 billion worth of contracts from 2004-2010 before being purchased by GEO Group—the “world’s largest private prison company.” BI generated over $1.6 billion in profits during its first year under GEO Group and now produces monitoring technologies for over 900 federal, state, and local agencies (Law & Schenwar 2020, p 41).

The web of capture does more than trap us inside it; it latches onto us and expands itself via capital investment. This is particularly true given the socioeconomic demographics of those of us whom it captures. Companies profit through contract convict labor; through commissary, telephonic communications, and other resources inside facilities; and through healthcare contracts. Drugs, medication, and substance dependency feed the punishment industry. This dependency is then facilitated inside through neglectful but profitable providers. We will discuss in our third report more of the ways those of us inside generate profit through the court and incarceration fees and services. Could all of this money be a deterrent to lawmakers and legislators to enacting sentence and prison reform? We think so. Could these profits have something to do with the ways our communities are criminalized and locked up by the thousands? We think so, too.

The numerous financial incentives for expanding the web of criminalization are perhaps most evident in cases involving drug dependency paired with long sentences – of which we saw many throughout our research. Joanna, who had rotator cuff surgery and was prescribed oxycodone for a long period of time, became dependent upon her medication. When she could not afford health insurance after her disability lapsed, she sought street drugs which was the cheapest route for continuing to manage her pain. She explains, “My quality of life diminished because I could no longer function without my medicine and the pain was unbearable” (Joanna interview 2019). Now sitting in prison, she is one of many that became trapped by drug laws despite getting hooked by legal prescriptions issued by suppliers who profited from her usage. She says, “No one offered me a drug program or physical therapy/pain management” (Joanna interview 2019).

While our experiences with targeted policing and the separation of our families speak to the forms by which the web has expanded, we include these points to also further our abolitionist lens toward reform. Law and Schenwar (2020) propose:

When evaluating whether reforms are helpful or harmful, a key question should always be: Are these reforms building up structures that we will need to dismantle in the future?

(p. 22)

Every single woman we interviewed has experienced some from of abuse and/or trauma. Most of this trauma has not been dealt with and being in and out of prison only perpetuates trauma and the cycle continues. Our community must choose people over profit and embrace compassion and support over imprisonment. So long as the targeting and blaming continues, we fail to see the very real problems we can solve through community collaboration and investment. We may sit here discarded, but our resilience embodies that commitment to ourselves and one another, and we intend to lead the way forward.

References

Alexander, M. (2012). The new Jim Crow: mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

American Civil Liberties Union. (2014). War comes home: the excessive militarization of American policing. New York.

https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/assets/jus14-warcomeshome-report-web-rel1.pdf

Bureau of Women’s and Children’s Health. (2020). South Mountain Village & Guadalupe Primary Care Area (PCA): 2019 statistical profile. Retrieved from

http://www.azdhs.gov/documents/prevention/health-systems-development/data-reports-maps/reports/datadocu.pdf

Cacho, L. M. (2012). Social death: racialized rightlessness and the criminalization of the unprotected. New York: New York University Press.

Casey, M., Jenkins, J., Maxedon, T., & Blokland, H. van. (2020). Boiling point: policing in Arizona at a crossroads. KJZZ 91.5. Retrieved from https://kjzz.org/content/1603805/boiling-point-policing-arizona-crossroads

Center on Media Crime and Justice. (2008). In some areas, high hidden local costs of incarceration. The Crime Report. Center on Media Crime and Justice at John Jay College. Retrieved from

https://thecrimereport.org/2008/07/10/in-some-areas-high-hidden-local-costs-of-incarceration/

Chicago PIC Training Collective. (2011) https://chicagopiccollective.wordpress.com/

Cloud, D. (2014). On life support: public health in the age of mass incarceration. New York. Retrieved from

https://www.vera.org/publications/on-life-support-public-health-in-the-age-of-mass-incarceration

Davis, A. Y. (1998). The Angela Y. Davis reader. Oxford: Blackstone Publishing.

Davis, A. Y. (2005). Abolition democracy: beyond empire, prisons, and torture. New York: Seven Stories Press.

Davis, A. Y. (2003). Are prisons obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press.

Davis, E., Whyde, A., & Langton, L. (2018). Contacts between police and the public, 2015.

Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpp15.pdf

DeVuono-powell, S., Schweidler, C., Walters, A., & Zohrabi, A. (2015). Who pays? The true cost of incarceration on families. Oakland: Ella Baker Center, Forward Together, Research Action Design. Retrieved from http://whopaysreport.org/who-pays-full-report/

Doleac, J. L. (2018, July 2). Study after study shows ex-prisoners would be better off without intense supervision. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2018/07/02/study-after-study-shows-ex-prisoners-would-be-better-off-without-intense-supervision/

Fagan, J., & West, V. (2010). Incarceration and the economic fortunes of urban neighborhoods. Columbia Public Law Research Paper. New York: Columbia University. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1772190

Fwd.us. (2018a). Arizona’s imprisonment crisis Part 1: the high price of prison growth.

Retrieved from https://www.fwd.us/news/arizona-imprisonment-crisis-part-1/

Fwd.us. (2018b). Arizona’s imprisonment crisis Part 2: the cost to communities.

Retrieved from https://www.fwd.us/news/arizona-imprisonment-crisis-part-2/

Fwd.us. (2018c). Arizona’s imprisonment crisis Part 3: the harm to women and families.

Retrieved from https://www.fwd.us/news/arizona-imprisonment-crisis-part-3/

Gilmore, R. W. (2007). Golden gulag: prisons, surplus, and opposition in globalizing California. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Grand Canyon Institute. (2016). Arizona spends too much incarcerating, too little on personnel, drug-treatment, transition services and higher education. [Press Release]. Retrieved from https://grandcanyoninstitute.org/news/press-release/arizona-spends-too-much-incarcerating-too-little-on-personnel-drug-treatment-transition-services-and-higher-education/

Greene, J. (2011). Turning the corner: opportunities for effective sentencing and correctional practices in Arizona.

Retrieved from http://davidshopeaz.org/resources/Turning_the_Corner.pdf

Hinton, E. (2016). From the war on poverty to the war on crime: the making of mass incarceration in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Justice Mapping Center. (2009). Million Dollar Blocks: Brownsville, Brooklyn. Justice Mapping

Law, V. (2009). Resistance behind bars: the struggles of incarcerated women. Oakland: PM Press.

Law, V., & Schenwar, M. (2020). Prison by any other name. New York: The New Press.

Lynch, M. (2009). Sunbelt justice: Arizona and the transformation of American punishment. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Lynch, S. M., Dehart, D. D., Belknap, J., & Green, B. L. (2012). Women’s pathways to jail: The roles & intersections of serious mental illness & trauma. Bureau of Justice Assistance.

Retrieved from https://www.bja.gov/publications/women_pathways_to_jail.pdf

McCorkel, J. A. (2013). Breaking women: gender, race, and the new politics of imprisonment. New York: New York University Press.

Morales, A. L. (1998). Medicine stories: history, culture, and the politics of integrity. Boston: South End Press. Center.

Police review board must represent the most-affected communities. (2020, July 1). Arizona Capitol Times. Retrieved from

https://azcapitoltimes.com/news/2020/07/01/police-review-board-must-represent-the-most-affected-communities/

Prison Policy Initiative. (n.d.) State profiles: Arizona profile. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/AZ.html

Ritchie, B. (2012). Arrested justice: Black women, violence and America’s prison nation. New York: New York University Press.

Rothstein, R. (2017). The color of law: a forgotten history of how our government segregated America. New York: Liveright.

Scahill, J. (Host). (2020, June 10). Ruth Wilson Gilmore makes the case for abolition. [Audio podcast episode]. In Intercepted. First Look Media. https://theintercept.com/2020/06/10/ruth-wilson-gilmore-makes-the-case-for-abolition/

Spatial Information Design Lab. (2008). The Pattern: Million Dollar Blocks. New York: Spatial Information Design Lab.

Retrieved from https://c4sr.columbia.edu/projects/million-dollar-blocks

Sudbury, J. (2005). Celling Black Bodies: Black Women in the Global Prison Industrial Complex. Feminist Review, (80), 162-179. Retrieved January 28, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3874373

Vedantam, S. (Host). (2016, November 1). How a theory of crime and policing was born, and went terribly wrong. [Audio podcast episode]. In The Hidden Brain. KJZZ 91.5 Phoenix.

https://www.npr.org/2016/11/01/500104506/broken-windows-policing-and-the-origins-of-stop-and-frisk-and-how-it-went-wrong

Vitale, A. S. (2018). The end of policing. Brooklyn: Verso.