Inside Arizona's Punishment System:

Part 2: Extreme Sentencing and the Abolition of Early Release

Table of Contents

For those of us

who were imprinted with fear

like a faint line in the center of our foreheads

learning to be afraid with our mother’s milk

for by this weapon

this illusion of some safety to be found

the heavy-footed hoped to silence us

Audre Lorde, A Litany for Survival

Introduction

In overcrowded jail cells, we wait to be sentenced, to be granted some semblance of stability after having been ripped from the outside world. Sitting on the cold concrete, trying to wrap our minds around the charges we were accused of, simultaneously we desperately wonder, “Where are my children at? Are they safe? Has my family been notified?” Worrying about our family’s terror regarding what just happened, all we can think about is the look on our children’s faces not having any understanding of what is going on. We head to the phones to face the chaotic lines, 30 people in a 12×12 cell, all praying that somebody will answer their calls on the other end. Our worries spiral to our pets, jobs, homes, caretaking duties, the car left on the side of the road. Little did we know that the next 24 hours would turn into years fighting for our lives. Our arrests occurred when we were struggling just to get by, when we finally stood up to our abusers, when we had been pushed by force or desperation into settings we never wished to find ourselves in. Our arrests mark the worst day of our lives—so far, perhaps.

For this second report in our four-part series, we articulate some of the forms of systemic abuse one faces once one reaches the sentencing stage of the Arizona punishment system. Although we are taught to naively believe in the sanctity of due process from trial to appeal, our research reveals instead a series of staggering institutional and extralegal forms of disempowerment and disavowal.

After experiencing the hardship and trauma so many of us report here, we are subjected to the severing of our families and relationships; intimidation and abuse by state officials seeking a conviction by any means necessary; and political and policy tribulations that ensure we will be entrapped in this system for as long as legally possible, and sometimes more.

This report, like our entire series, centers on the expertise and wisdom of those of us most unfortunately close to the problems at hand. In so doing, we reject categorizations of us that impose limits and qualifiers to whether or not we deserve dignified treatment. Instead, we embrace the radical notion that no one deserves the horrors of the punishment system; and we intentionally interrogate the sentencing structures and policies that most gravely result in a life in its entrapment.

We focus on the ones who are poor, who are afraid, who are the lifers, the sex offenders, the survivors. These are our people, and we are them. We are the ones whom this system most wants disposed, so we are here to expose the logics and hypocrisies of how that disposal occurs. It begins with arrest and the realization that we may never leave, no matter how hard we fight.

The Costs of Bail

As a constitutional right, we should be presumed innocent until proven guilty; but once arrested and detained, your pre-trial innocence becomes dependent on whether or not you are able to afford your bail.

According to recent data from the Prison Policy Initiative, roughly 74% of the over 630,000 people currently held in U.S. jails have not yet been convicted (Sawyer & Wagner 2020). This population comprises “virtually all of the net jail growth in the last 20 years,” reflecting the financial and policy driven expansion of criminalization. There are more people spending longer stretches in costly pre-trial detention precisely because they lack financial resources for bail.

The ACLU Smart Justice project argues that this conundrum presents a serious threat to the constitutional protections of due process and the right to a speedy trial under the Fourteenth and Sixth Amendments, as well as the prohibition against excessive bail included in the Eighth Amendment (American Civil Liberties Union, 2019).

Defendants face an impossible choice: sit in jail as the case moves through the system; pay a nonrefundable fee to a for-profit bail bonds company; or plead guilty and give up the right to defend themselves at trial.

(ibid.)

The Context of Bail Assessments

The United States and the Philippines are the only countries in the world that operate commercialized, for-profit bail industries (Bauer, 2014). There was a national movement during the 1960s to dismantle the bail system, including research indicating it was unnecessary to ensure defendants’ presence in court. The 70s and 80s then broadened capacity for bail systems, a result of timely policy shifts reflecting an increased—and racialized—fear of crime (Sykstra 2018).

Even these shifts ostensibly deemed pre-trial detention a “carefully limited exception” to the practice of granting freedom until proven guilty (ibid.; the term is codified in United States v. Salerno, decided in 1987). In practice, however, “between 1990 and 2009, releases in which courts used money bail in felony cases rose from 37 percent to 61 percent” (ibid.).

In order to address bail discrepancies, Arizona approved a Public Safety Assessment (PSA) tool in 2015, which allows courts to quantify factors like flight risk, record, and age in order to recommend “fairer” bail amounts if bail is to be used at all. In 2016, the National Task Force on Fines, Fees, and Bail Practices was initiated to review court-ordered fines, penalties, fees, and pretrial release practices (National Task Force on Fines, Fees, and Bail Practices, 2019).

In Arizona, this task force consulted local grassroots organizations for recommendations, with a key focus on the ways bail extends the disproportionate burdens borne by local communities of color.1 The effect of their recommendations – and whether or not they were truly considered – has yet to be formally measured through public accountability.

1. These groups included Puente Human Rights Movement, Justice that Works, Center for Neighborhood Leadership, Guadalupe Municipal Court, Mesa Municipal Court, and the Maricopa County Probation Office.

The bail system in Arizona extends the broad right of pre-trial freedom to all defendants, but this right is granted discretionarily based on charges imposed by the prosecutor. Particular charges require a compulsory denial of bail and courts may expand this denial for other charges based on the use of a PSA and their judgment regarding the defendant (“Changing rules”, n.d.). While bail may be revoked as decided, it may not be granted discretionarily. Donna’s charges disqualified her from pre-trial release, leaving her imprisoned from the moment of arrest to the writing of this report (Donna Interview 2019). She, like many others, had to spend this time fighting her case while simultaneously navigating the new uncertainties of her life, house, work, and of children from whom she was suddenly and indefinitely separated.

Even when granted a bail option, many of our participants were unable to afford such a costly and uncertain deposit, especially in addition to the costs arising from the sudden loss of income and support inherent to their abrupt imprisonment. These burdens are especially damaging for those already struggling with economic hardship prior to their arrest, as “the median bail amount for felonies is $10,000, which represents 8 months’ income for a typical person detained because they can’t pay bail” (Sawyer & Wagner 2020).

Being imprisoned indefinitely despite retaining legal innocence has its costs to those inside, who are subject to one to three years of substandard medical care, inadequate nutrition, and dangerous environments, often pushing us to accept pleas simply to leave. But these costs gravely affect our families too. Zumaya was arrested for fraudulent check writing during a time when she was already unable to support her family. Once charged, her bail was insurmountably higher than she could afford, forcing her to remain in pre-trial detention. Because of this imprisonment, Zumaya was abruptly pulled from providing for her family—having lost her work, she could not contribute to mortgage payments and lost her home. Her children faced the largest loss, however, as their mother was unnecessarily ripped from their lives for years before she was even convicted (Zumaya Interview 2019).

Exaggerated Charges

Our research reflects the ways structural and discretionary actions on the parts of prosecutors and judges often result in charges that are extreme and retaliatory. Prosecutors have the capacity to set charges that mean the difference between being granted bail, or being detained pending trial. These decisions also mean the difference between a sentence of probation, jail or prison time, and post-release parole and/or probation. The distinction between scaled charges is entirely out of our hands. For example, prosecutors of common drug possession often inflate the charges to a sales or transporting charge in order to allow the highest possible sentencing opportunity. This expansion of charges can increase the severity from a class 6 felony to a class 3 felony or higher; the difference between the two punishments is the difference between probation and a prison term.

Prosecutors and judges can also decide to stack sentences consecutively rather than run them concurrently. When sentences run consecutively, the defendant serves them back to back. When they run concurrently, the defendant serves them at the same time. For example, a person is given five years on count 1, and three years on count 2. If that person was sentenced consecutively, they would serve a total of eight years. If they were sentenced concurrently they would serve five. Choosing between consecutive or concurrent sentencing is often the result either of arguing aggravating circumstances or of ‘prioring’ charges within the same case number, also known as “Hannah priors.” Hannah priors refer to several offenses that stem from the same, singular incident. The conviction on all offenses can serve as “priors” for purposes of “repetitive offender status,” which would place an individual into a higher sentencing bracket.

The decision to charge in a particular way (i.e. aggravating circumstances, prioring) is less about the facts of the case and more about the presumed character of the defendant. This is why sentencing is raced, classed, gendered.

Sometimes, aggravating circumstances and prioring are both deployed to ensure maximum sentencing outcomes.

When Angie, who was a teenager at the time, went to trial, she was scared to reveal that she had escaped the physical and sexual abuse that she had been subjected to since the age of 8 by running away. When she discussed this abuse at trial, it was dismissed as a falsehood and she was characterized as an incorrigible runaway, pathological liar, and drug addict by her prosecutor, Jeanette Gallagher. This was further exacerbated by a character statement given by one of her abusers, which prompted her judge, John Leonardo, to aggravate her charges. Angie divulged her history of childhood physical and sexual abuse and explained that she ran away to escape abuse in the hopes of finding compassion and support for the survivor that she is. Angie reflected, “Where’s a runaway kid supposed to go? To the police? They would’ve sent me right back!”

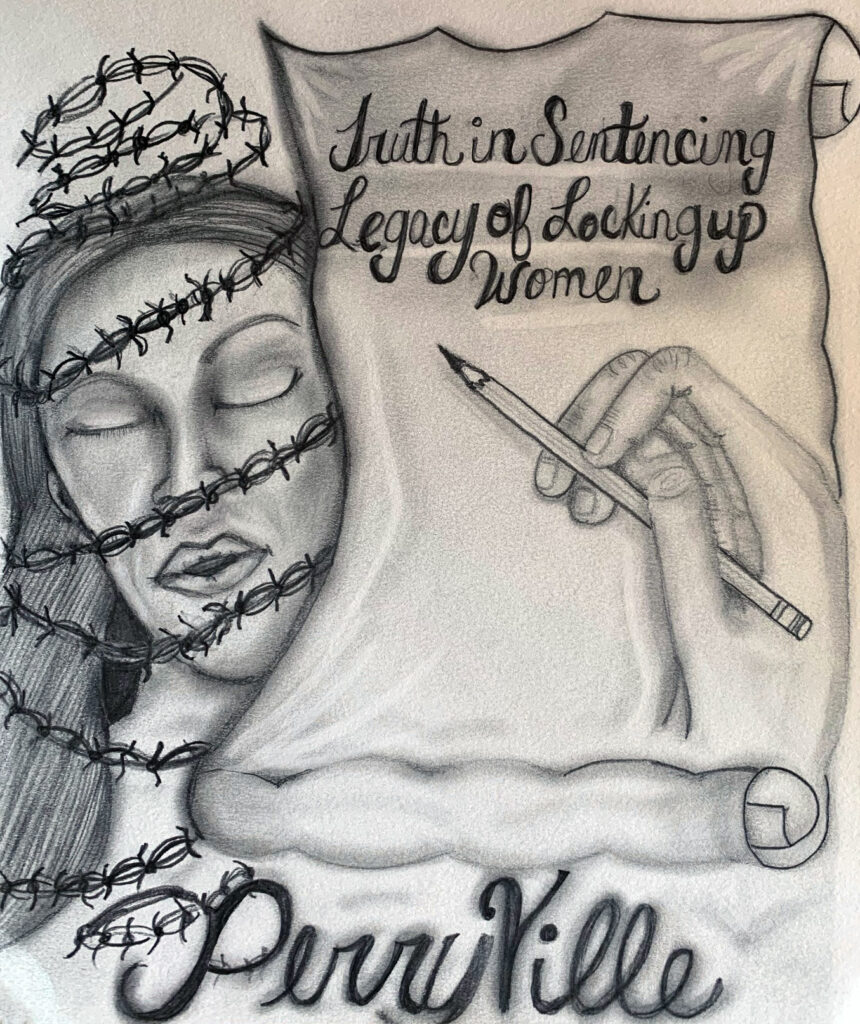

Despite it being her first encounter with the justice system, she was painted as a “delinquent.” Angie’s judge priored her on multiple charges after her first charge within the same case. This further portrayed her as a “repeat offender.” As a result, Angie was convicted as an adult under Truth in Sentencing, a subject we will return to later in this report. Angie’s sentences were then made consecutive and she was given a total sentence of 61 years. She was 17. At the time of this report, she is 45 and still facing another 33 years in Perryville (Angie Interview 2019).

Nicole was also sentenced to consecutive sentences at her judge’s discretion—and retaliation. She was offered a plea of 10 years for her peripheral involvement in a felony murder case. The felony murder rule is an outdated legal doctrine that holds a person liable for first degree murder if a death occurs during the commission of certain felonies. This law, like so many, disproportionately impacts youth of color and women. While the evidence was clear that Nicole was not even present at the time of the incident, she was ultimately sentenced to two consecutive 25 year sentences totaling 50 years in prison.

Nicole’s original plea deal was contingent upon her testimony against her co-defendants, two of whom were her brothers. When she found out that the prosecutor planned to use her testimony to elevate her brothers’ charges to capital, seeking the death penalty, she refused to testify. Nicole could not bear to be the used as a shovel to dig her brothers’ graves. She rejected the deal and asked for a trial, based on the facts of the case, as well numerous statements by the prosecution and the judge that she was barely if at all culpable. But as is often the case when someone asks for a trial after being offered a plea deal, the terms suddenly shifted. That her punishment was retaliatory is clear from the statement the judge made at her sentencing:

Now when the Judge is sentencing me, he sentences me—and this is on record—he says: ‘The reason why I am sentencing you to consecutive sentences is because you refuse to bring the murderers forward. So therefore,’ he says, ‘it’s as if you pulled the trigger yourself.’ That was his reasoning for giving me consecutive sentences, because I didn’t testify? Are you serious?

(Nicole interview, 2019)

What should have been Nicole’s constitutional right to request a trial by a jury of her peers resulted in blatant repercussions and the loss of most of her life to this system. Nicole was only 22 when she was sentenced to 50 years in prison. At the time of this report, she is still seeking appeals after already serving 27 years.

Overcharging to Secure a Plea

H. Mitchell Caldwell argues that overcharging constitutes “the precursor to coercive pleas” by using this process to create undue leverage in order to avoid a costly and time consuming trial as well as to secure a conviction:

If our criminal justice system were trial-centered, prosecutors would only have reason to file charges on which they would likely secure a conviction. However, because most criminal convictions are secured through plea negotiations, prosecutors have an incentive to file more serious charges than those supported by the evidence with the ‘hope that a defendant will be risk averse.’ Furthermore, prosecutors lack any political incentive to refrain from overcharging because most communities want the state to be tough on crime. (Caldwell 2012)

The practice of inflicting exaggerated charges for ideological or political reasons is unfortunately commonplace. Overcharging a defendant is perhaps the most direct way for prosecutors to attempt to secure a plea and therefore a conviction. The leverage created by initially extreme charges compels a defendant to accept the lesser, though still exaggerated charges contained in a plea agreement, for fear of facing the extreme punishment at trial (ibid.).

Manipulative Investigation and Prosecution

To be captured within the punishment system is a traumatic and shameful experience. From the circumstances that led to arrest, to the actual arrest and interrogations with police, to court proceedings, we are disempowered and alone at every turn. Many of our participants reflected on the feeling of sinking with nothing to solidly grab onto or drowning in a sea of defenselessness and uncertainty. The system is designed to shame, punish and exploit. Our research indicated ample evidence of abuse and intimidation from state actors, investigators, and prosecutors. Given that for most of us, our autonomy is revoked the moment we are arrested, we are trapped in a position of passivity, largely unaware of our rights and without means to challenge the misconduct of officials with vast power over our lives.

A Culture of Impunity

The state’s drive to coerce a confession, state’s evidence, and a guilty plea is a vicious one. And yet “aggressive and often unethical conduct” like the experiences our participants shared has come to be emblematic as part of the “decades-long culture of misconduct that flows from the top down, one that prioritizes winning convictions over pursuing fairness and executing justice.” This toxic pattern is what prompted the ACLU to file an amicus brief in 2019 urging further investigation of prosecutors within the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office (Arcenaux & Keenan, 2019; In Re Juan M. Martinez, 2020).2 Even former prosecutors from the department like Rick Romley have described the prevalence of this misconduct as “mindboggling” and far from unique to a handful of attorneys (ibid.).

That said, those explicitly named in the ACLU’s statement as egregious examples—Juan Martinez, Noel Levy, and Jeannette Gallagher—prosecuted a handful of our twenty-six interviewees. The result of this “crisis of impunity,” the statement reads, “has been a deep, unremitting harm not only to defendants, and especially those wrongfully convicted, but to the actual and perceived fairness and integrity of Arizona’s courts” (ibid.). This injustice is exacerbated when racial patterns are examined. The most recent Smart Justice report from 2020 concludes that Black and Latinx Maricopa County defendants are sentenced at vastly disproportionate rates than whites, whose cases are also far more likely to be dismissed than other groups’ (Ortiz & Kovacs, 2020).

2. See the press release regarding this action, written by Jared Keenan from ACLU-AZ and Anna Arceneaux from ACLU Capital Punishment Project. Amicus brief here.

Most of the participants in our research indicated that they knew very little if anything about their rights prior to their entrapment in the system. The pressure tactics used by state investigators and prosecution are wide-reaching, and while limits may technically exist, our experiences speak for themselves. Family manipulation, leveraging of relationships, public shaming, and physical intimidation were common among many of the women we spoke with.

In one of the most appalling accounts of these tactics, Nicole described how the state withheld her children, questioned them, and refused to tell her where they were unless she gave them information. Nicole was arrested and brought to county jail, where she immediately called her mother to see if she had her children. Her mother did not. Panicked, Nicole waited on word that her children were somewhere safe. “They said, ‘Nicole, you have a visit,’” she recalled, “So I’m thinking it’s my mom coming to tell me that she has my children” (Nicole Interview 2019). Once in the visitation area, Nicole met the detectives and came undone.

I started crying, asking him, where are my kids? Where are my kids? And he starts laughing. He goes, ‘oh, you want to know where your kids are now?’ He said, ‘okay, I’ll tell you what: you tell me what I want to know and I will tell you where your kids are.’

(Nicole interview, 2019)

Nicole was emotional just recounting her fear that day. She agreed – on record, without a lawyer, and without her rights recited – to tell them anything they wanted to hear in exchange for information about her children. She found out later that her children, ages 5 and 6, were in custody and being questioned alone. “They brought them some Happy Meals, my daughter said, and they gave them stuffed animals and asked my daughter if she saw anything and if she heard anything… They questioned my children without my consent” (Nicole Interview 2019). Nicole’s daughter is now 32 and can clearly remember that day and how scared she was.

Nicole’s children continued to be a bargaining chip for her prosecutor. Later in a sentencing hearing where she was supposed to plead guilty to the charges in her plea agreement, she couldn’t. As is often the case with pleas, the charges reflect the “deal” of lesser offenses even when it means listing charges that in no way resemble the defendant’s actions. She explained:

“The judge said, ‘I need you to tell me, Ms. Smith, how you kidnapped the two victims in your case with a gun, and took them from point A to point B.’ I said ‘but I didn’t kidnap anybody.’ I said, again, ‘I wasn’t even there. I’ve never held a gun in my life. I said, look at me—I’m 4’11”. I weigh 90 pounds!’ And he said, well why are you pleading guilty to kidnapping? And I said, because the prosecutor and my attorney are telling me that I need to take this plea in order to be able to be with my children again. And he said, ‘woah, we gotta stop this.’ The prosecutor was pissed. (Nicole interview 2019)

Agents acting on behalf of the state’s case face virtually no regulations or repercussions for their conduct in efforts to secure a conviction. According to the ACLU, prosecutors only very rarely incur any sanctions by the State Bar, and such appeals only occur in death penalty cases. Since none of our participants were sentenced to death, the misconduct of their prosecutors goes unchecked. In fact, Levy and Gallagher have both received Lifetime Achievement Awards from the Arizona Prosecuting Attorney’s Advisory Council (APAAC) and Martinez has received multiple “Prosecutor of the Year” accolades (Arcenaux & Keenan 2019; AMICUS).3

Keenan and Arceneaux from the ACLU write:

This culture of impunity is so entrenched that prosecutors not only escape discipline for misconduct and unethical behavior, they are, in fact, rewarded in spite of it… the absence of accountability has only encouraged young prosecutors to emulate these veteran attorneys in the office.

(ibid.)

This perception of justice and efficacy is not only lost to defendants; several of the women we spoke with expressed a frustration from the victims in their cases, whose interests were not represented by prosecution. The Victims’ Bill of Rights is located in Article 2 Section 2.1 of the Arizona Constitution, and includes provisions in Sections (A) 4 & 6 granting the victim the rights “to be heard at any proceeding involving a post-arrest release decision, a negotiated plea, and sentencing” and “to confer with the prosecution, after the crime against the victim has been charged, before trial or before any disposition of the case and to be informed of the disposition” (Arizona Const. art. 2 § 2.1(A) 4 & 6). However, it also stipulates in Section (B) that the victims’ rights will never supersede the state’s decision to convict and sentence the defendant as it determines (Arizona Const. art. 2 § 2.1(B)). This divergence demonstrates the overriding authority of the state to seek justice even where the alleged victim does not seek it.

The victim in Donna’s case was the father of her child, and he spent her court proceedings pleading with prosecution to not give her prison time. He was aware that Donna was facing charges because he had lied to her about his age, and she had believed him. Her defense team presented polygraphs, photos, statements, and other evidence to demonstrate the reasonableness of Donna’s perception. When this evidence was considered, expert witnesses determined his age appeared to be 23. Regardless, Donna was charged with knowingly participating in a relationship with a minor. Her victim tried to keep Donna from facing time. “He actually went in there to go talk to the prosecutor and speak with her face to face,” she said. “She completely ignored that he was there.” When the prosecutor continually refused to meet, he turned to Donna’s defense team and went on record stating: “I do not want the mother of my child to get prison time” (Donna Interview 2019). He also asked that his name be removed from the victim’s advocate center. The statement and all notes concerning this conversation were passed over to the prosecutor’s office, but none of it was considered at Donna’s sentencing.

The state’s forceful seeking of a conviction typically means isolation, family intimidation, and an inability to consider the victim’s wishes. These practices, which have become normalized, even incentivized among County Attorneys, further illustrate the central function of the punishment system to disconnect the state’s “justice” from other restorative or transformative approaches that center the actors involved in the alleged harm. These prosecutorial norms are designed and maintained by prosecutors, whose aims “reflect a ‘win at all costs’ mentality even when it runs afoul of prosecutors’ duty to act as ministers of justice” (In Re Juan M. Martinez, 2020). The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers noted the echoing effect such behavior has when recourse is so illusory:

Prosecutorial overreaching and misconduct distort the truth-finding process and taint the credibility of the criminal justice system, including the outcomes they generate. When prosecutors’ fundamental obligations are ignored and individuals’ rights are violated in order to secure a conviction, little can be done to rectify the wrongs inflicted upon the individuals involved and on the system itself.

(“DOJ on Prosecutorial Misconduct”, 2019)

Ineffectual Defense and Judgment

Our appointed counsel and presiding judge are our only real sources of defense against the predatory process of state prosecution. We navigate investigation, plea negotiations, trial, and sentencing with limited oversight regarding the adequacy of our defense and the impartiality of our judge. In many ways, the sentencing process initiates us into the next phase of our capture: in which we are completely dependent upon and at the disposal of state actors with varying degrees of concern for their power over our health and futures. We hope that our defense and judgment will reflect this concern, while recognizing both structural and subjective impediments to our dignified treatment.

Arizona Public Defender Caseloads

In 1984, the Arizona courts determined the maximum allowable caseloads for full-time defense attorneys employed by the state in State v. Joe U. Smith. These stipulate different yearly maximum loads for felonies (150), misdemeanors (300), juveniles (200), mental commitments (200), and appeals (25). These numbers are commonly referred to as the “Joe U. Smith guidelines.” Then in 1996, the next substantial legal shift came in with Zarabia v. Bradshaw, which affirmed that “assigning an attorney incapable, for whatever reason, of providing effective assistance at these stages [trial and on appeal] violates a defendant’s constitutional rights” and “an attorney has the ethical obligation not to accept such an appointment” (Stookey & Hammond, 1996).

Immediately following Zarabia, John Stookey and Larry Hammond reviewed survey data collected by the Yuma County Superior Court on caseloads in 13 Arizona counties and found vastly different standards (or lacks thereof):

The survey revealed, for example, that four of Arizona’s counties could not even estimate the average caseload for their criminal contract attorneys or public defenders. (Apache, Gila, Greenlee, Santa Cruz). Six additional counties estimated that each of their indigent defense attorneys was handling more than 200 combined criminal and misdemeanor cases per year. (Cochise, Coconino, La Paz, Mohave, Navajo, Yuma.) Maricopa, Pima, and Pinal counties reported that their average caseload per indigent defense attorney was in the area of 200 per year. Only Graham and Yavapai Counties reported a caseload substantially less than 200. (Stookey & Hammond, 1996)

Regarding competency for taking on such cases, they found that only one county required criminal law experience, while the rest “had no expressed standards for bidders, or the standard was merely ‘in good standing with the Arizona Bar Association’” (ibid.). Indigent defense attorneys are currently estimated to represent over 80% of felony defendants, while 90-95% of defendants with a public defender plead guilty rather than go to trial (Buckwalter-Poza 2016).

If appointed an attorney by the court, we have no control over who will be sitting beside us fighting for our life. For the overwhelming majority of our participants, the assignment of a public defender was our only option. Many of us were fortunate enough to have determined advocates on our defense; others were less fortunate. The stories we heard reflected expediency over accuracy, personal conflict between defense and prosecutors, and inaccurate legal interpretation. The consequences land on us, who remain defenseless to challenge them.

Trina’s case had been all but settled. Prior to her sentencing hearing where she was expected to accept a plea for 10 years, her public defender got into an argument with her prosecutor. They had just worked on another trial that had concluded in favor of the defense. In response, Trina’s prosecutor suddenly revoked the 10-year plea and replaced it with one for 20 years. This rivalry resulted in another decade added to an already extreme sentence, and Trina could do nothing to challenge it.

Winter ended up sentenced to life for a crime she not only did not commit, but during which she was held under gunpoint by her codefendant. Both the judge and prosecutor pushed Winter to take her case to trial and use the defense of duress. “The prosecution just said they don’t think I’m culpable,” she said, “The judge says take it to trial. My attorney is saying, why would you do anything but take this case to trial? So I’m not entertaining anything else at this point” (Winter Interview 2019).

After two weeks of trial and discussion of duress, however, Winter was told a grave mistake had been made – at her expense. While she was being brought to the courtroom, Winter heard her attorney and judge arguing loudly. The judge had determined that her defense of duress was invalid, according to Arizona law, if the circumstances resulted in serious physical injury or death. This revelation did not occur until the end of the trial, just before jury deliberation. Winter was powerless to challenge it. Her defense attorney attempted to motion for mistrial, but the judge blamed his legal ignorance and, in order to make clear that this defense was not valid and hammer in her attorney’s mistake, the judge instructed the jury against Winter. “Whether or not you find the defendant was held under force or threat of a weapon of any kind,” they reiterated, “you must find her guilty.” She continued:

So my jury goes out with this instruction for three days. They deliberate not on my guilt or my innocence. They deliberate whether they have to obey the judge’s instructions. The one and only question they asked to the judge was: ‘do we have to obey your instructions?’ He of course says yes. So they file and they find me guilty. They ask to change their verdicts; he ignores them. They filed affidavits saying they were confused by his instructions because they never felt I was guilty.

(Winter interview, 2019)

Winter has sought multiple appeals regarding this course of events, but while the Arizona Supreme Court concluded her judge acted in error, it was determined to be “harmless” and insufficient for appeal. From whom was Winter’s life sentence harmless? For herself, her son, or her parents? The answer is tragically unclear. The consequences of judicial and defense counsel floundering can be devastating.

In cases wherein a judge feels that a sentence is excessive—typically as a result of mandatory minimum sentencing schemes—they may issue a special order under ARS 13-603L allowing the individual to petition the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency for commutation of sentence within 90 days of initial sentencing. While portrayed as an act of leniency or compassion, the ineffectual nature of this order and of the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency (ABOEC, discussed in detail below) results only in false hope. In reality, this form of redress is structurally impossible in Arizona.

Among the many participants we interviewed who had received a 13-603L for an excessive sentence, everyone received the same rejection from the ABOEC on grounds that they could not prove sufficient “rehabilitation.”

While this stipulation appears tangential to the question of excessive sentencing, the Board uses it as a means to systematically deny every 13-603L-based petition it receives. And while all parties recognize that sufficient programming, employment, and service is not possible to obtain within 90 days of imprisonment, the petition based on this order is required within this timeframe. At best, this process is deceptive; at worst, it is designed to make it impossible to appeal a sentence that even the sentencing judge deems excessive. We will further discuss the broad gatekeeping authority of the ABOEC to refuse all releases later in this report.

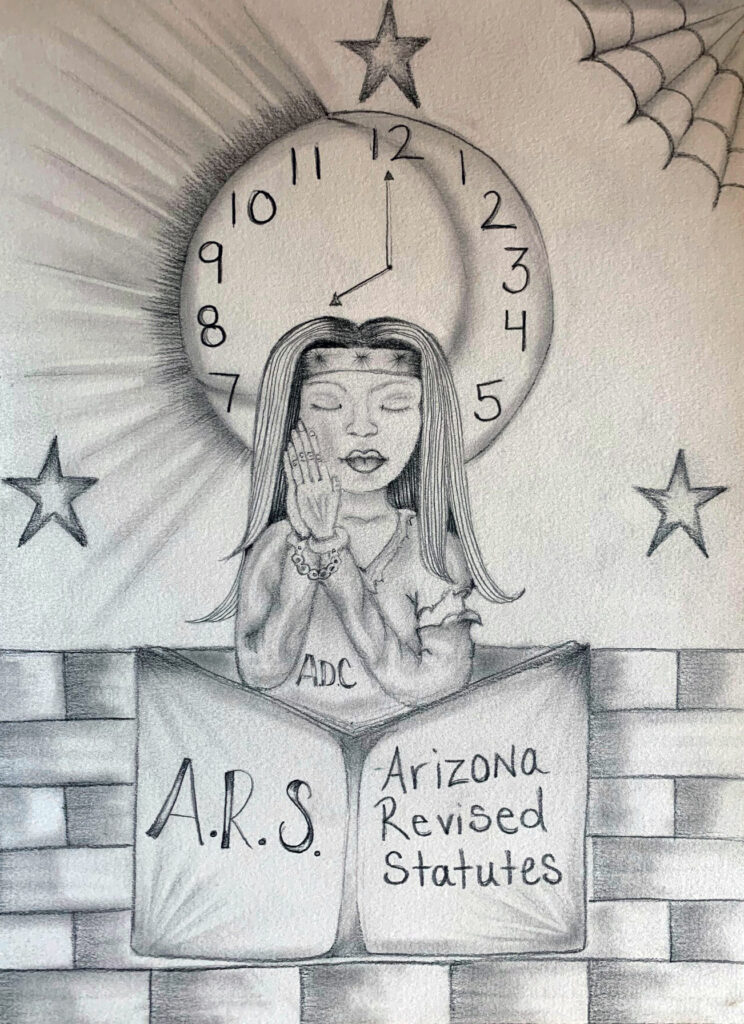

Truth in Sentencing

As we discussed in our first report, “The Web of Criminalization,” mass incarceration in the U.S. has grown through racially differentiated policing, largely promoted under the guise of “law and order” and at the expense of social welfare. National reforms laid significant groundwork for the racially motivated sentencing policy shifts to come starting in the mid-1980s up until 1994. This period saw the boom in prison construction, incarceration rates, and sentence lengths, all as a direct result of sentencing policies.

As resistance to economic and social inequality increased during civil rights and anti-war protests, so too did racist stereotypes linking race, poverty, and criminality. This imagery culminated in the direct policy integration of policing in Black and Brown neighborhoods, including programs that categorized youth as “potential criminals.” Policy shifts under the powerful Law Enforcement Assistance Administration altogether replaced the Office of Economic Opportunity under President Nixon (Hinton 2016).

The introduction of determinate sentencing laws, or set sentencing and mandatory minimums, were marketed as a turn toward fairer, more predictable sentences. Their execution, however, further entrenched existing racial disparities that “reached extreme and unprecedented levels” (Travis, Western & Redburn 2014). Determinate sentencing and mandatory minimums served to increase both conviction rates and sentence lengths; yet, only three states—Minnesota, North Carolina, and Washington—chose to implement “population constraint” policies in order to “ensure that the number of inmates sentenced to prison would not exceed the capacity of state prisons to hold them.” Arizona did nothing tonstrain its rapidly increasing prison population. In fact, Arizona implemented its first mandatory sentences in 1978, only one year after Harris v. Caldwell resulted in a federal mandate for incarceration reduction due to unconstitutional levels of overcrowding in Florence (Lynch 2010).

By the early 1990s, “law and order” had morphed into politically popular “tough on crime” campaigns, first promoted by George H. W. Bush and then mimicked by Bill Clinton in an effort by the Democratic party to gain moderate conservative support. Clinton’s presidential campaign marked a Democratic party effort to demonstrate that they, too, could take on typically Republican issues such crime and welfare reduction. Echoing this ideology, special interest groups on both sides of the political spectrum began funding the push for mandatory minimum sentences across the nation.

By 1994, every state in the U.S. had adopted mandatory minimum sentencing schemes. As a critical shift, “mandatory punishments transfer dispositive discretion in the handling of cases from judges, who are expected to be non-partisan and dispassionate, to prosecutors, who are comparatively more vulnerable to influence by political considerations and public emotion” (Travis, Western & Redburn 2014). The political message of being tough on crime was overt even in the highest of legal authorities. Then-Attorney General William Barr, who returned in the latter part of the Trump administration, urged an increase in both the number of people in prison and prison construction, in a preface to a U.S. Department of Justice report titled The Case for More Incarceration in 1992 (ibid.; Schlesinger & Himmelfarb 1992).

The most expansive—and devastating—sentencing reform also came in 1994. Authored by Joe Biden (then senator, now president) in consultation with the National Association of Police Organizations, Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. Under this policy, mass incarceration was openly promoted and incentivized with federal grants for states that implemented policy changes specifically designed to increase, and mandate, lengthier sentences; dramatically grow police departments; and build new prisons.

In order to qualify for grant consideration, states had to meet Truth in Sentencing standards. Truth in Sentencing is “a 1980s neologism” referring to the requirement that at least 85% of sentences are served and parole eligibility and early release credits are restricted if not eliminated (Travis, Western & Redburn 2014). “The implication [of truth in sentencing] is that there is something untruthful about parole release and other mechanisms that allow discretionary decisions about release dates to be made” (ibid.). In total, the 1994 Crime Bill, as it has come to be known, authorized $8 billion for the explicit purpose of new prison construction. Twenty-eight states and the District of Colombia successfully met harsher sentencing guidelines to access these funds and expanded their systems of incarceration (ibid.).

Arizona accumulated $57,923,000 over a five-year period under the 1994 Crime Act and Truth in Sentencing stipulations. In line with these requirements, Arizona’s policy changes included the abolition of parole and the stipulation that no less than 85% of sentences be served. Additionally, these funds were allocated for the construction of new medium and maximum-security bed space.4 When Arizona ceased receiving grant funds, the costs of maintaining such an inflated state punishment system were transferred from other public services and tax revenue.

4. Arizona State Senate Issue Brief: Truth in Sentencing, 2010.

Today, Arizona remains a vast outlier in its continued use of Truth in Sentencing standards. This is the only state that mandates that 85% of all sentences be served. Arizona also maintains mandatory sentencing schemes which have been reformed in many other states. The “ostensible primary rationale is deterrence,” a National Research Council assessment states regarding such determinate sentencing schemes developed under Truth in Sentencing: “The overwhelming weight of the evidence, however, shows that determinate sentences have few if any deterrent effects” (Travis, Western & Redburn 2014). The effect they have undoubtedly had is a vast expansion of the punishment system, nationally and certainly in Arizona.

The Center for American Progress reports that “in the decade following the Crime Bill’s enactment, the number of correctional facilities nationwide jumped by 20%. The incarcerated population grew by 40% during the same period” (Chung, Pearl and Hunter, 2019). Between 1985 and 1994, as a result of new mandatory sentences, Arizona’s incarcerated population grew 132% (from 8,531 to 19,746). From 1994 to 2018, as a result of Truth in Sentencing measures, it grew another 113% (from 19,746 to 42,005). The rate of incarceration of women in Arizona outpaced even this rate of growth, rising 221% and then another 230% from 1985-1994 and 1994-2018, respectively (Bureau of Justice Statistics 1987; Beck & Gillard 1995; Carson 2020).

Life with or without Parole

Marie Gottschalk has described life imprisonment as “death in slow motion” (Gottschalk 2012). Kenneth Hartman describes “the sense of being dead while you’re still alive, the feeling of being dumped into a deep well struggling to tread water until, some 40 or 50 years later, you drown” (Hartman 2016). These visceral descriptions acutely describe what has come to be utilized as the humane alternative to a death sentence.

Life sentences play a large part in mass incarceration in the United States. One in every seven people currently incarcerated is serving a life sentence (Nellis & Mauer, 2018). This number is even higher among incarcerated Black Americans, one in every five of whom is sentenced to life. The total number of people serving life sentences today is greater than the total number of incarcerated individuals at the onset of the mass incarceration era beginning in the early 1970s (ibid.).

Of the over 200,000 people currently serving a life sentence in the U.S., 50,000 are not eligible for parole (1 in 4). Ashley Nellis and Mark Mauer contextualize this particularly U.S. American pheomenon:

Fifty people were serving a sentence of life without parole in the United Kingdom as of 2015. Thus, the United States, which has about five times the population of the United Kingdom, has more than one thousand times the number of people serving life without parole.

(Nellis & Mauer, 2018)

Moreover, the use of life sentences for children—with or without parole and including “de facto” life sentences, or those over 50 years—is largely distinct to the U.S. Twelve states alone hold 8,300 prisoners serving life sentences received as children (Van Zyl Smit & Appleton, 2018).

Nationally as well as locally, the effect that life sentences and contradictory changes in law have had on our communities is devastating. This is seen perhaps most clearly among those in Arizona sentenced to life with a possibility of release, who have had that possibility rescinded by Arizona’s Truth in Sentencing changes.

The abolition of parole has left us without a mechanism for early release in the state of Arizona for the past 28 years. Significantly, this has left lifers with no means for a prescribed or earned release opportunity.

There are currently hundreds of individuals in Arizona whose sentences include the promise of a parole board, stipulated in both trials and plea agreements. As Michael Kiefer exposed through his Arizona Republic investigation in 2018, this scandal has been referred to as “Arizona’s dirty little secret.” (Kiefer 2017). Since the abolition of parole in 1993 up until the present, the state of Arizona has continued to sentence people to indeterminate sentences, most often 25 or 35 years to life. To execute this sentence, however, a parole board must be available to be convened after that time elapses, in order to consider release. “The only problem,” Kiefer writes, “It doesn’t exist” (ibid.).

Nevertheless, over the past 28 years, prosecutors and judges have repeatedly sent people down a dead-end path to non-existent parole, resulting in hundreds currently incarcerated indefinitely until the state determines whether and how to honor the contracts signed at sentencing. Depending on whether these sentences were given as a plea or a trial verdict, as well as minute variations in sentencing language that confound the differences between a “chance of parole” and “chance of release,” only a small subset of people indefinitely incarcerated can access relief currently—and only upon individual appeal using case precedent.

Myra was pressured into accepting a plea for 25 to life. She resisted signing, because like many others, she could not honestly plead guilty to the murder charges she was facing as a result of the felony murder net. Her attorney threatened her mother that Myra would die in prison if she did not sign. Myra acquiesced, for her mother’s sake. Now she is unclear whether the terms she signed will be honored. This is even more unclear because of the inconsistencies in her sentencing language. She explained:

I have three separate verbiages in my paperwork. One piece of paper says life for first degree murder. One piece of paper says life with the possibility of parole after a mandatory minimum of 25 calendar years. One says life with the possibility of release, after the mandatory 25. So I’m not real certain. I’ve asked my lawyer to write me and at least tell me what it was that my judge had actually said. I have not yet heard anything.

(Myra interview, 2019)

The distinctions between these phrases is key. Whereas “parole” is the conditional release of a person incarcerated to community supervision by a parole officer, “release” is only possible through petitioning for sentence commutation or pardon from the Governor through the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency. The problem with this route, as Kiefer points out, is that “release” is “illusory” via clemency in Arizona, as recognized by both Arizona appellate courts and federal courts in 2014. “Life with release,” he writes, “pretty much amounted to life with no chance of parole because there really was no mechanism to be released” (Kiefer 2018).

V also signed a sentencing contract for “25 to life with the eligibility of parole after 25 years.” It wasn’t until several years ago that she too found out that parole did not exist in Arizona. “Now I’m approaching my 25th year,” she said, “and I have no idea what’s going to happen to me. I do know that I do not want to go to clemency… with the politics that are involved and the harshness of my sentence, I feel like before I go in there, decisions would already be made.”

Lanae was sentenced to 25 years with a chance of release, which she also recognizes is a false replacement for parole;

I found out parole no longer exists. I was not told that when I was being pressured to take a plea. There’s a ‘chance’ of release, which is based on the Governor’s decision, which would be political suicide for him. So my ‘chance of release’ is nonexistent.

(Myra interview, 2019)

While Arizona has legislatively remedied this issue for juveniles, it is dragging its heels for the rest of us. The U.S. Supreme Court decided in 2012 in Miller v. Alabama that sentencing a child to life without parole violates the Eighth Amendment protection against cruel and unusual punishment. In 2016, the Court in Montgomery v. Louisiana applied the Miller decision retroactively, tasking states with executing a means for release hearings for all those currently serving sentences of life received as juveniles. In Arizona, this pre-emptively triggered a policy response in 2014, when HB 2193 designated parole board dates for these individuals. It should be noted that, despite these reforms, a large segment of the juvenile lifer population was omitted: juveniles sentenced to “de facto” life. Angie, who was sentenced at 17 to flat time, still has no relief in sight until her scheduled release at the age of 79; her sentence does not legally equate to a life behind bars.

For the rest of us charged as adults, it was not until March of 2020 that Chaparro v. Shinn concluded that the original wording of vaguely “25 to life” sentences, including access to the abolished parole system, must be honored despite the lack of this relief upon original sentencing. This decision does not automatically designate parole board dates for all those currently incarcerated, however, and the State has yet to legislatively address it. Instead, each individual is left to fight for the contractual terms they signed—most often wagered by prosecutors as plea agreements—through a costly and uncertain appeals process citing Chaparro, or face their luck with the Governor.

Even if lifers are granted the opportunity for a parole board, as we will further discuss in our next report, internal Department of Corrections policies prohibit us from engaging in many programming and employment opportunities vital to demonstrate to the board that we should be granted release. Around every turn, it seems there is another wall.

Felony Murder

The felony murder law facilitates the wide arrest of all persons associated with the commission of a felony in which an individual dies, no matter how that death occurs. The U.S. is the only nation where this doctrine still exists, since its abolition in England in 1957 (“Know More: Felony-Murder”, n.d.). Six U.S. states have thus far abolished it (Gullapalli 2019). While the intention appeared to be to deter dangerous behavior that would reasonably be expected to risk the life of another, it has resulted in widespread homicide charges for those who, willingly or unwillingly, are even tangentially present during what are often dramatically unforeseen consequences. Under the felony murder doctrine,

All participants in the felony can, and most likely will, be held equally liable—even those who did no harm, had no weapon, and had no intent to hurt anyone. 5

Agency v. Proximate Cause Theory in Arizona

This is especially true in Arizona, which follows a proximate cause felony murder statute: felony murder applies when a person has committed any of a number of offenses “and, in the course of and in furtherance of the offense or immediate flight from the offense, the person or another person causes the death of any person” (ARS 13-1105). Proximate cause theory holds defendants accountable for any and all deaths—even those caused by third parties—during or in flight from the felony. Agency theory, by comparison, does not include culpability for third party actors (“Know More: Felony-Murder”, n.d.). Due to our state’s extensive application of the proximate cause theory, “Arizona’s felony murder rule has been described as the broadest in this country.” Further, “the Arizona legislature also makes clear that no mental state is required other than the commission of the enumerated felony.” Arizona’s statute thus “codifies the principle that malice needed for the murder is transferred from the commission or attempted commission of any of the enumerated felonies” (Birdsong 2007).

Almost all the women we interviewed who are lifers were sentenced under the felony murder law. Extreme sentences are the result of the elevation of all participation to murder charges. First degree murder is typically the primary charge, while pleading to second degree or manslaughter are sometimes alternative options.

The Felony Murder Elimination Project out of California notes that felony murder “eliminates the prosecutor’s burden of proving intent or premeditation to kill—elements which must be proven for first-degree murder—thus making it the easiest murder conviction for a prosecutor to win.”

(ibid.)

As we discussed in our first report, nearly all incarcerated women have faced physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and manipulation prior to their arrests; felony murder, more than any other statute, comprises a legal means to punish women for being in these situations in the first place. Of course, not all felony murder charges are levied at women whose presence is over-determined by violence. Many of the stories we heard simply include haphazard actions that misapply intention where none exists. The following represent shockingly common applications of the felony murder statute that have all resulted in life sentences. And as outlined in the previous section, these women also face indefinite futures as their sentences include the nonexistent promise of parole.

Earlier in this report, we shared Winter’s sentencing experience wherein her judge instructed her jury to ignore her defense of duress in order to find her guilty under the felony murder statute. As her case exemplifies, many women are here despite the fact that their lives were being threatened during these situations.

Winter had been struggling to quit heroin after her abusive ex got her hooked on it. He convinced her that it would take longer and be more painful to use methadone and told her to wean herself off using small doses of heroin instead. Two of her ex’s friends were over and presumably helping her acquire more, when they decided to attack the dealers upon their arrival. One turned a gun on Winter and forced her to go to another room to collect restraints. Winter remained frozen at gunpoint while the murder occurred in her house.

She was arrested and charged with felony murder—even though her culpability was not in question, she was held under the threat of deadly force, and no transaction even occurred—because she was guilty of the felony of making a phone call to purchase narcotics that day (Winter Interview, 2019).

Myra, like Winter, was held hostage during the incident for which she was charged. She was picked up hitchhiking by a man who held her with him while he exacted revenge on a man Myra did not know. After a week of “surviving off of flaming hot Cheetos, Dr. Pepper, and meth in my veins,” (Myra Interview, 2019), Myra was taken in a van along with this man into the middle of nowhere late at night. Myra explained;

My codefendant told the victim to get out and take off running. I got out of the van and gave him a sweater. I thought he was walking.

(Myra interview, 2019)

Myra returned to the passenger seat. She recounted; “As we start to move, my codefendant tells me: when I tell you to roll down your window, I want you to roll down your window. So, I asked him, what? He said, when I tell you to roll down your window, I want you to roll down your window. So, he told me to roll it down and I rolled it down… And then all of a sudden, I hear the shots and I see what feels like a fire in front of my face” (Myra interview, 2019).

When they returned to town, Myra stole a car in order to escape. She was arrested and charged with 1st degree capital murder but was able to reduce this to felony murder and avoid the death penalty only if she agreed to testify. She did and was sentenced to life.

Lily was also charged with felony murder because of proximity rather than intent or culpability. Lily had a brief interaction with individuals in her house who were having a conflict in the living room. She returned to her bedroom, where she heard the incident occur. The sound still haunts her today, as was evident when she recalled it to us. Lily was not aware of what felony murder meant, and, like Winter, chose not to sign a plea because she could not admit to something she did not do. Likewise, she was scared for her family if she took a plea in exchange for her testimony: “I had people following and attacking my family that knew my codefendant,” she said. “That’s just the way you grow up, that really isn’t an option. So, I turned that down, went to trial, and was convicted” (Lily Interview, 2019).

Lanae and V were charged with felony murder after another party pulled a trigger during their commission of property felonies. In most U.S. states, they would not be culpable; in Arizona, they were both charged with first degree murder. Lanae and her boyfriend attempted to rob a convenience store for cash. There was an altercation with the store clerk, and he acquired Lanae’s boyfriend’s gun. Now unarmed, they started to retreat. The clerk fired shots, severely injuring Lanae and killing her boyfriend. Lanae was sentenced to life for her boyfriend’s death (Lanae Interview, 2019).

Similarly, V and her co-defendant intended to steal a car parked in front of a Circle K. They watched as the owner of the car spotted them as he left the store. They decided to bolt. While they were sprinting away, unarmed, the owner of the car acquired a gun from his vehicle and began firing in their direction as they fled. He shot and killed a bystander crossing the parking lot between them. V was charged for the death of the bystander, while the shooter was not charged (V Interview, 2019).

None of these are exceptional stories. Arizona employs the most severe and expansive application of felony murder charges, in the only nation in the world that still allows this outdated and problematic doctrine.

Arizona Board of Executive Clemency

Federal Truth in Sentencing guidelines did not mandate the elimination of parole, but in order to meet funding conditions, many states chose to do so – including Arizona. These stipulations required states to demonstrate that 1) they were sentencing more people; 2) to longer average times; and 3) guaranteeing that an increased percentage of that time would be served before release (Travis, Western & Redburn, 2014). The abolition of parole took these tasks even further, entrenching us in a system whereby release is made impossible once the state’s sentence has been dealt.

The Elimination of Early Release Inflates Prison Populations

Since the 1994 Crime Bill, most states that followed the parole abolition route had found themselves with excessively inflated state prison systems, little effect on crime rates, and severely taxed local governments no longer receiving federal funds. As early as 1999, commentators saw that these issues were causing some states to immediately reconsider reinstating parole, despite the “politically popular step” it had represented, noting: “three states… reinstituted parole boards after eliminating them because the resulting increase in inmates crowded prisons so much that the states were forced to release many of them early” (Butterfield 1999).

Many states have since reformed sentencing structures and reinstated parole boards after significant evidence of the explosive effect this had on prison populations. As of today, parole remains abolished in sixteen states, including Arizona. A 2019 report by the Prison Policy Initiative grading states’ early release systems gave Arizona an F-. Their study included considerations regarding the kind of access and representation people were provided, the transparency and guidelines used for consideration for release, and the degree of assistance provided to prepare for such hearings. Suffice it to say, Arizona’s decision to eliminate any possible early parole releases made these factors ultimately irrelevant (Renaud 2019).

When the parole board was eliminated in 1993, it was replaced by the Arizona Board of Executive Clemency (ABOEC). This entity only functions as a parole mechanism for “old code cases” including parole prior to its abolition, as well as those cases for whom parole relief was federally mandated by the U.S. Supreme Court decision regarding juveniles sentenced to life (a process legislated in AZ in HB 2193). For all those sentenced after 1994, parole in Arizona is nonexistent—even for those whose sentence tells them they will see a parole board after a given amount of time.

Parole v. Release and Equal Protection

For those sentenced to life with a possibility of parole after 25 years, as discussed above, the state has shrugged its shoulders at the lack of existing parole process. These individuals are generally categorized into four groups: those whose sentencing language stipulates “parole” or “release,” further categorized by those signed at trial or through a plea. As of today, those who signed a plea agreement specifically using the word “parole” (as opposed to “release”) will be granted the opportunity to appear before the ABOEC, functioning as a parole board. As of the recent case precedent in Chaparro v. Shinn, an individual’s sentencing order (rather than sentencing transcripts, or what the judge actually informed the defendant of at sentencing) must also use the word “parole” to be certified; all sentences designating “life,” “25-to-life,” or any other verbiage – including the word “release” – need not be honored with a parole opportunity. This hair-splitting process is motivated by the state’s goal to hear as few of these cases as legally permissible, so as to appear tough on crime and reticent to allow any opportunity for early release. And this is an ongoing fight for equal protection actively being waged by those of us directly impacted by this issue.

Whereas the parole process in many states, and formerly Arizona, generates automatic hearing dates determined by an individual’s charges, disciplinary record, and participation in programming (Earned Release Credits), the ABOEC functions entirely on a case-by-case, application basis. That is to say, we must now apply for and be granted a clemency hearing, instead of coming up for parole automatically after a certain amount of time. And despite any amount of work or programming, we may never apply for parole as is possible in most U.S. states.

The ABOEC Board is made up of 5 individuals who are appointed by the Governor. These Board appointments often reflect the political incentives of the sitting Governor, which in Arizona generally means conservative and “tough on crime.” Moreover, it is only up to the ABOEC to make recommendations; the Governor must sign off on any possible pardons or commutations. As of 2020, Governor Doug Ducey had granted only one pardon and nine commutations during his five years in office. Eight out of those nine commutations were for individuals with terminal illness who had less than four months to live (Leingang 2018; “Arizona Inmate’s Release”, 2020).

These numbers are even more disheartening considering that between 2015-2017 alone, the ABOEC heard 989 individual petitions (Arizona Board of Executive Clemency, 2017). The problem is clearly shared between the ABOEC and the Governor, who together ensure that:

Statistically, if you are convicted of a felony in Arizona, you are more likely to be struck by lightning than granted clemency.

(Ortega 2012)

The process goes like this: We can petition to the ABOEC for consideration for commutation of sentence, and if accepted, we move first to Phase 1: a public hearing allowing no speakers, no legal representation, and no personal participation. One member of the Board reads the application against the original facts of the case aloud, considering only one factor: whether the judge’s sentence seems excessive based on the presumptive sentence, which specifies an appropriate or “normal” sentence guideline to be used as a baseline for a judge in sentencing in comparison to a maximum sentence, which represents the outer limit of a sentence according to its A.R.S. code. The presenting Board member situates this comparison and then asks if any members of the Board have comments. One of our outside co-researchers attended several days of hearings and did not witness a single comment to follow the presentation – no discussion, no questions. After a few moments of silence, the presenting member suggests rejection and asks if all are in favor. A disinterested chorus of “aye” replies.

That’s how Donna’s Phase I hearing went. Her legal team and family were barred from speaking and her application was read, considered, and rejected in less than six minutes.

The Board has broad authority to ensure harsh sentences are fully served, even when this authority contradicts the order from the sentencing judge asserting that the mandatory sentence was excessive. Terry shared with us: “I used my 13-603L six times and my 135 years apparently was not excessive in their eyes, while my plea for only 17 years was not even considered because I chose to go to trial” (Terry Interview, 2019). Between 2015-2017, the ABOEC rejected every petition based on a 13-603L order from a sentencing judge (Arizona Board of Executive Clemency, 2015; 2016; 2017).6 Terry’s case also demonstrates the punitive consequences of going to trial over accepting a plea, a discrepancy not considered once the sentence has been handed down— not even upon consideration for commutation.

6. 2017 is the last year for which the ABOEC has revealed data.

Of the 964 cases the ABOEC heard for Phase I between 2015-2017, only 17 were passed on to the next stage in the process, a Phase II hearing—that’s less than 2%. In this stage of hearing, legal representation and supporting materials are allowed, and we may briefly speak on our own behalf. That is, if those extremely slim odds are in our favor. At this hearing, the board decides whether or not to recommend clemency to the Governor—the last step.

During this time period, the ABOEC only sent 7 recommendations for commutation to Ducey’s desk. He approved zero. (Arizona Board of Executive Clemency, 2015; 2016; 2017). By 2020, he had approved one—for a prisoner who had already served 50 years (Polletta 2019).

Applicants may fast track their petition to Phase II for reason of “imminent danger of death,” the cause for Governor Ducey’s only other granted commutations. To qualify for this designation, documentation must certify “with a reasonable medical certainty” that a person’s death will occur within four months (FAMM 2018). The exact time frame for this designation is inconsistent. The Arizona Department of Corrections requires that death must be expected within three months; ABOEC lists four months; and the State’s pardon process states that six months is the requirement (ibid.).

Of the eligible applicants for this relief from 2015-2017—individuals asking only to be granted the ability to die at home—the ABOEC rejected 60% (Arizona Board of Executive Clemency, 2015; 2016; 2017).

And then there are some terminally ill applicants who are deemed ineligible before ever reaching the ABOEC, left to die in prison because they have not yet served enough of their sentence to have ‘earned’ release.

We met Erika Kurtenbach for an interview in December of 2018, when we first began this project. She came to us to share her story and to ask for advice. She had recently been transferred to the yard, and upon arrival was handed an application for clemency, “for medical reasons” (Erika Interview, 2018). Confused, she was told she had to ask the Deputy Warden, who informed her that she was given the application due to her terminal diagnosis. This was how Erika found out that she was dying. After years of pleading with Perryville medical care to conduct critical tests and treatments, their neglect had allowed her initially very treatable cancer to metastasize. It was projected to kill her within months.

And yet, after serving 20 years, Erika would not be released to be with her mother and daughter for her final weeks. She submitted the completed petition and it was returned to her in less than a week. She was instructed to consider re-applying in five years, at the requisite 25th year in her 25-to-life sentence. Her A.R.S. code designated that she was ineligible for any type of early release for any reason, including imminent danger of death.

Erika tragically and needlessly died in Perryville in March of 2020. She was only 42. Our hearts ache with despair and rage as we write this.

Conclusion

This system is heinous. There is no way around this fact. Erika’s heartbreaking death followed after decades of dehumanization under the Arizona punishment system. Threatened by a prosecutor seeking her execution, charged with first degree felony murder for her presence under threat of her life, sentenced under Truth in Sentencing to 25 to life despite the nonexistence of parole, killed by prison medical mistreatment, and refused even the opportunity to die with her family by her side… This is not the entirety of Erika’s beautiful life – but it is what the state of Arizona did to her.

We demand action in Erika’s memory.

References

American Civil Liberties Union. (2019). Bail reform. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from

https://www.aclu.org/issues/smart-justice/bail-reform

Arcenaux, A., & Keenan, J. (2019, April 4). We are fighting Maricopa County’s rampant prosecutorial misconduct. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/blog/smart-justice/prosecutorial-reform/we-are-fighting-maricopa-countys-rampant-prosecutorial

Arizona Board of Executive Clemency. (2015). Annual Report 2015. Retrieved from

https://boec.az.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/Annual Report PDF 2015.pdf

Arizona Board of Executive Clemency. (2016). Annual report fiscal year 2016. Retrieved from

https://boec.az.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/2016 Annual Report.pdf

Arizona Board of Executive Clemency. (2017). Annual report fiscal year 2017. Retrieved from

https://boec.az.gov/sites/default/files/documents/files/Annual Final Report.pdf

Arizona inmate’s release held up by molestation allegation. (2020, January 22). AZFamily.Com. Retrieved from https://www.azfamily.com/news/ap_cnn/arizona-inmate-s-release-held-up-by-molestation-allegation/article_b25b54d2-3d10-11ea-9ebb-cfb3ad14703c.html

Bauer, S. (2014). Inside the wild, shadowy, and highly lucrative bail industry. Mother Jones. Retrieved from

https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2014/06/bail-bond-prison-industry/

Beck, A. J., & Gillard, D. K. (1995). Prisoners in 1994. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, (August), 1–16. Retrieved from

https://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/Pi94.pdf

Birdsong, L. (2007). The felony murder doctrine revisited: a proposal for calibrating punishment that reaffirms the sanctity of human life of co-felons who are victims. Ohio Northern University Law Review, 33. Retrieved from

https://ssrn.com/abstract=2513609

Brief for American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona and American Civil Liberties Union as Amici Curiae In Re Juan M. Martinez, (no. SB-17-0081-AP), 2020.

Buckwalter-Poza, R. (2016, December 8). Making Justice Equal. Center for American Progress, pp. 1–9. Retrieved from

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2016/12/08/294479/making-justice-equal/

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (1987). Correctional Populations in the United States 1985. Retrieved from

https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus85.pdf

Butterfield, F. (1999, January 10). Eliminating parole boards isn’t a cure-all, experts say. New York Times.

Carson, E. A. (2020). Prisoners in 2018 – BJS. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin, (April), 1–37. Retrieved from

https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p18.pdf

Changing rules for bail bonds. (n.d.). AZLawHelp. https://www.azlawhelp.org/articles_info.cfm?mc=13&sc=98&articleid=398

Chung, E., Pearl, B., & Hunter, L. (2019, March 26). The 1994 Crime Bill continues to undercut justice reform—here’s how to stop it. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/criminal-justice/reports/2019/03/26/467486/1994-crime-bill-continues-undercut-justice-reform-heres-stop/

Ditton, P. M., & Wilson, D. J. (1999). Bureau of justice statistics special resport: truth in sentencing in state prisons.

https://bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/tssp.pdf

DOJ on prosecutorial misconduct. (2019, April 25). National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. Retrieved from

https://www.nacdl.org/Content/DOJonProsecutorialMisconduct

FAMM. (2018). Executive clemency due to imminent danger of death. Washington DC. Retrieved from https://famm.org/wp-content/uploads/Arizona_Final.pdf

Gottschalk, M. (2012, January 15). Days without end: life sentences and penal reform. Prison Legal News. Retrieved from

https://www.prisonlegalnews.org/news/2012/jan/15/days-without-end-life-sentences-and-penal-reform/

Gullapalli, V. (2019, September 23). The felony murder rule as a “representation of what’s wrong in our criminal legal system.” The Appeal. Retrieved from

https://theappeal.org/the-felony-murder-rule-as-a-representation-of-whats-wrong-in-our-criminal-legal-system/

Hartman, K. E. (2016, October 23). Death by another name. The Marshall Project. Retrieved from

https://www.themarshallproject.org/2016/10/23/death-by-another-name

Hinton, E. (2016). From the war on poverty to the war on crime: the making of mass incarceration in America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Kiefer, M. (2017, May 19). Hundreds of people were sentenced to life with chance of parole. Just one problem: It doesn’t exist. The Republic, Azcentral.Com. Retrieved from https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-investigations/2017/03/19/myth-life-sentence-with-parole-arizona-clemency/99316310/

Kiefer, M. (2018, January 22). Bill would ban life sentences for juveniles in Arizona. The Republic, Azcentral.Com.

Know more: felony-murder. (n.d.). Retrieved January 30, 2021, from

https://restorejustice.org/about-us/resources/know-more/know-more-felony-murder/

Leingang, R. (2018, March 9). Ducey record on pardons, commutations not forgiving. Arizona Capitol Times. Retrieved from

https://azcapitoltimes.com/news/2018/03/09/arizona-doug-ducey-pardons-commutations-not-forgiving/

Lynch, M. (2009). Sunbelt justice: Arizona and the transformation of American punishment. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

National Research Council. (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: exploring causes and consequences. Washington DC. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/18613

National Task Force on Fines, Fees and Bail Practices. (2019). Bail Reform: A Practical Guide Based on Research and Experience.

Nellis, A., & Mauer, M. (2018). The meaning of life: the case for abolishing life sentences. New York: The New Press.

Ortega, B. (2012, May 12). Arizona prisoners rarely granted clemency: Governor seldom uses sentencing “safety valve.” The Republic, Azcentral.Com. Retrieved from http://archive.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/news/articles/20120412arizona-prison-clemency.html

Ortiz, A., & Kovacs, M. (2020). The racial divide of prosecutions in the Maricopa County Attorney’s office. Retrieved from

https://www.acluaz.org/sites/default/files/7.16embargofinal_the_racial_divide_2020.pdf

Polletta, M. (2019, November 27). In rare move, Arizona governor reduces sentence for man convicted for murder almost 50 years ago. The Republic, Azcentral.Com.

Renaud, J. (2019, February 26). Grading the parole release systems of all 50 states. Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved from

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/grading_parole.html

Sawyer, W., & Wagner, P. (2020, March 24). Mass incarceration: the whole pie 2020. Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved from

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html

Schlesinger, S. R. & Himmelfarb, E. (1992). U.S. Department of Justice Office of Policy and Communications, Office of Policy Development: The Case for More Incarceration, NCJ-139583.

Stookey, J. A., & Hammond, L. A. (1996, October). Rethinking Arizona’s system of indigent representation. Arizona Attorney. Retrieved from https://www.myazbar.org/AZAttorney/archives/Oct96/toc.htm

Sykstra, S. (2018, October 17). Bail reform, which could save millions of unconvicted people from jail, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2018/10/17/17955306/bail-reform-criminal-justice-inequality

Travis, J., Western, B., & Redburn, S. (2014). The growth of incarceration in the United States: exploring causes and consequences. (J. Travis, B. Western, & S. Redburn, Eds.). Washington DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/18613

Van Zyl Smit, D., & Appleton, C. (2018). Life imprisonment: a policy briefing. Life Imprisonment.

https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674989139